The Coffins of Ancient Egypt

by Jimmy Dunn writing as Jefferson Monet

One of the most important objects purchased, whether for royalty or other elites, for a tomb was the coffin. It's purpose from the earliest times was the protection of the body, preserving it from deterioration or mutilation. During Predynastic times, the Egyptians shrouded corpses in mats or furs and enclosed them in pots, baskets or clay coffins. In some areas a wooden scaffold was constructed around the body, and this might be considered the precursor to actual coffins.

A sarcophagus was also usually provided to hold the coffin in the tomb. The Greek etymology of "sarcophagus" is "flesh eater". However, this is not really the Egyptian interpretation. In their ancient language, the sarcophagus might be called neb ankh (possessor of life). There are several other words for coffins and sarcophagi, but perhaps the most relevant to this discussion are wet and suhet. We do not precisely understand the meaning of wet, though it appears to be derived from the words for "mummy bandage" and to embalm. The Egyptians were (and continue to be) attracted to word play, so it is likely no coincidence that another word, wetet, which would have sounded similar, meant "to beget". In other words, from the coffin the deceased will be reborn. This pun is strengthened by the word suhet, used for "inner coffins" or perhaps "mummy board". This is also the word for "egg", from which new life emerges (and hence its association with Easter).

In their preparation for rebirth after death, particularly later in the New Kingdom, the wealthy ancient Egyptians might prepare themselves by purchasing a sarcophagus (possessor of life), a coffin (the bound mummy, or "that which begets"), and an inner coffin or mummy board (the egg). Coffins could, at various times over the long period of pharaonic history, be made of wood, metal or pottery. Different workshops undoubtedly varied in their respect for tradition and other aspects of coffin production. Hence, various forms of mummy containers often existed contemporaneously, and this was particularly true for the intermediate periods. Between these, during the periods of Egyptian stability, the coffins were more standardized.

The first clearly established royal coffins date to the 3rd Dynasty, and some of these made of stone have been preserved. They were often very plain, with a flat cover, though some are more elaborate with vaulted lids and crosspieces. However, there was considerable differences between coffins belonging to private individuals as opposed to royalty, obviously due to the limited resources available to most of the deceased. Royal burials were often equipped with various funerary equipment and objects, while private individuals might instead have such objects painted on their coffins and on the interior walls of their tombs.

In fact, coffins and coffin walls were decorated from a very early date. The first decorations were false doors and false-door facades, which first appeared on wooden coffins of the 2nd and 3rd Dynasty, and later on royal and private sarcophagi of the Old Kingdom. There was a transition during the 5th and 6th Dynasties, when Unas became the first king to decorate the interior walls of his tomb with Pyramid Texts and false door facades. Private individuals of that period also began to decorate their tombs interiors, though in a different style then royalty, with scenes of everyday life. However, the coffins remained relatively plain, at most having a pair of eyes (so that the deceased could see) and horizontal bands of hieroglyphs on the outside, and on the inside, a false door, lists of offerings and more bands of hieroglyphs.

As with portraits, coffin styles and decorations changed over time. The earliest were made of wood and were basically rectangular boxes. This type of coffin remained common through the Middle Kingdom, though it was then that the anthropoid-shaped coffins first appeared as an inner container for the body placed within the rectangular outer coffin.

During the Middle Kingdom, Lower (northern) Egyptian coffin styles became relatively homogeneous, while Upper Egyptian styles were more variable. During the 11th Dynasty, coffins were almost always positioned in a north-south orientation. The Lower Egyptian coffins, known as "standard class coffins", often had a false door through which the dead can step out to the offering site painted on their interior east walls, with a pair of eyes painted on the outside to enable him to see the activities at the offering site. Osiris was then mentioned in the offering spell on the outside eastern side of the coffin, followed by a plea for offerings to the dead. On the inside were painted offerings and a list of offerings, rather than a depiction of the offering ceremony. The western side of the coffin was decorated with the burial scene, where the god Anubis was included in horizontal bands of hieroglyphs, followed by a plea by the deceased for a beautiful burial.

During the 11th Dynasty, there was often a frieze of objects shown on the western side and on the narrow sides of the coffin. They mostly include objects of everyday life, such as jewelry, weapons and clothing. There are often Coffin Text copied onto the interior sides of these coffins, though not restricted to a specific side. During the 12th Dynasty, the most significant innovation was the transfer of friezes of objects onto the east side of the coffin and the addition of vertical lines on the exterior sides. Now, additional objects are shown in the friezes, and even new classes of objects are found.

During the Middle Kingdom, Upper (southern) styles were less standard than those in the north, and demonstrated strong local characteristics. Cities such as Asyut, Akhmin and Thebes developed their own very distinctive styles. They are mostly decorated on the exterior sides and have freely depicted representations of human figures.

In addition to these styles, there is also a type of coffin from this period called the "court style", which was reserved primarily for members of the royal family. Court coffins were adorned with bands of hieroglyphs in a very simple style. On some coffins, the corners and bands of the hieroglyphs are embellished with gold leaf.

The anthropoid coffin became standard with a very distinctive style during the Second Intermediate period. Like mummification, they also provided an image, or qed (form), of the deceased that could house not only his corpse, but also his spirits. Their lids were at first decorated all over with representations of the vulture's wings. Known as rishi (from the Arabic meaning "feather") coffins, they were either painted or, as in the case of Queen Ahhotep, plastered and then gilded. Of course, Egypt's intermediate periods were difficult times between the empire's more outstanding dynasties, and often precious raw materials were in limited supply. Hence, royal coffins such as those of Ahhotep and Nubkheperre Intef VII had only a thin layer of gold over a plaster base that itself covered a roughly hewn log coffin.

After the Second Intermediate period during Egypt's grand 18th Dynasty, anthropoid coffins were first painted white with crisscrossed bands imitating mummy wrappings. Their sides were often painted with the same scenes found in tombs. An inscribed vertical band was painted in the middle of the lid which then descended to the edge of the feet, and four transverse bands were painted on both sides of the lid and case of the coffin, in imitation of the mummy bandages. Painted panels of Osiris, Anubis and the Sons of Horus are sometimes represented between the texts, but the most typical iconography of these coffins shows various burial themes, such as the transport of the mummy, mourners, offering rituals and so on. On the lid, at breast level, a figure of the protecting goddess (Nekhbet or Nut) is usually depicted.

However, by the middle of the dynasty, around the time of Hatshepsut, coffins were more commonly, particularly in non-royal burials, covered with black pitch. This background was then interrupted by bands, running vertically down the front and horizontally as well. The best of these had gilded faces, and the bands were of gold. The iconography of these coffins was constant, consisting of a winged figure on the lid, the Four Sons of Horus, and Thoth and Anubis on the walls of the case. They were most common in Thebes, but were also found in Memphis and the Fayoum. Wealthy individuals may have had outer and inner nested coffins of this type. In fact, the model coffin for Amenhotep Huy's ushabti represents this type of coffin, although the color was green rather than black. Green was also a color symbolic of resurrection to the ancient Egyptians, and was easier to achieve in faience then black.

During the New Kingdom, most of the wealthy acquired multiple coffins for their burials, as well as sarcophagi to hold them. The sarcophagi were most frequently topped by pitched roofs, imitating the archaic icon of the Egyptian shrines of Upper Egypt. They were equipped with sleds, so that they could be more easily dragged by oxen across the desert to the cemetery.

Those of lower status were buried in single coffins, usually made from cheap materials such as pottery or reeds, though occasionally, richly equipped mummies were buried in single wooden coffins. Nested coffins consisting of up to four coffins were restricted to the middle and upper class burials. These complex coffins could be made of various materials and in different shapes, though the finest wooden coffins were made of cedar, while others were made of sycamore or acacia. Gold and silver were reserved for kings, while even gold or silver gilding usually indicated the owner's relationship to the king or a high priest's family.

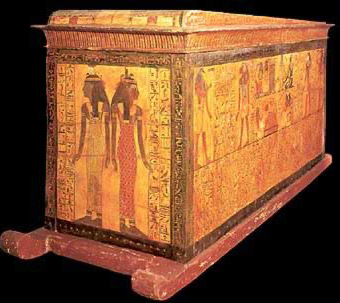

A sarcophagus with on runners from the 19th Dynasty

Later in the New Kingdom, particularly during the 19th and 20th Dynasties, the black resin coffins were replaced with coffins having a yellow background and brightly painted representations of the gods of the afterlife. These coffins were covered with vignettes associated with the spells of the Book of the Dead, such as Chapters 1, or 17, which are illustrated with the lions of the horizon and the embalmer's tent among other scenes. These "yellow" wooden coffins, attested from both Thebes and Memphis, have figures and text painted in red and light and dark blues. In the anthropoid coffins, the carved forearms were crossed at the breast. On those belonging to men, the hands clenched sculpted amulets, while those of women are open and lie flat on their breasts.

The mummy in these coffins were often covered with a "false lid", known as a mummy board, which most often imitates the shape of the lid. This mummy board consisted of two pieces. The

upper part represented the face, collar and the crossed arms, while the lower pieces, frequently made in an openwork technique, imitates the network of mummy bandages, with figural scenes filling the panels between the bands.

In the early 19th Dynasty, a new type of mummy board and lid was used. It depicted the deceased as a living person, dressed in festive garments, with the hands of men placed on the thighs, while those of women were pressed to the breast and holding a decorative plant. Some of these lids were fashioned in stone for the anthropomorphic sarcophagi of high officials.

These styles of coffin with polychrome scenes continued beyond the New Kingdom, but in the 21st Dynasty, the themes represented were greatly expanded. This was a period when tomb building almost ceased in Thebes and the Valley of the Kings was abandoned, so coffins for most private people became an even more important aspect of the deceased's hopes for the next world. Only anthropomorphic coffins are known from this period, mostly from Thebes, and mummy boards were made of wood in one piece and are usually of the "Osirian" type.

The last decade of Ramesses XI's reign brought revolutionary changes in iconography, and while the old motifs, such as the Four Sons of Horus, Isis and Nephthys as mourners never really disappeared, a great number of new scenes were introduced. New compositions were added, often with emphasis on solar religion combined with the myth of Osiris. These new scenes focused on cosmological deities such as Geb and Nut, with illustrations of the gods' journey through the netherworld, the revival of the mummy and the triumph over the Apophis serpent. Each scene includes both solar and Osirian elements, illustrating the solar-Osirian unity as the theological principle of the period. These scenes were supplemented by various offering scenes covering every surface of the coffin except the exterior of the bottom.

By the end of the 21st Dynasty, coffins were no longer predominantly yellow, but might be red or other colors such as white or light blue. Much of the iconography appearing on these coffins was a result of the royal status gained by the high priest Menkheperre. The scenes on coffins could now include vignettes from the Amduat or perhaps rituals associated with the king, such as the sed-festival.

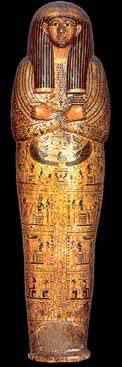

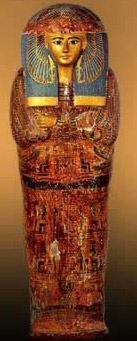

Anthropoid coffin of Paduamen, with inner board and lid

In the Third Intermediate Period, coffins continued to change, though there was little visible impact from the early years of Libyan rule in Egypt. Even the yellow type of coffin persisted in Thebes until the reign of Osorkon I. They often were made with a foot pedestal so that the mummy could be placed vertically (though these were not unknown in earlier coffins). The multicolored, varnished decoration on a white or yellow background utilized motifs such as wings, the sacred emblem of Abydos, and the Apis bull with a mummy on its back. Now, the backs of the coffins were often decorated with the djed symbol, meaning "stability", but here implying the strong backbone of Osiris.

However, the political chaos of the middle and late Libyan period generated a diversity of forms and decorative motifs. There were various shapes and decorations on coffins from different workshops. Now we find coffins of traditional anthropoid form, with a case deep enough for the mummy, covered with a flat or convex lid. However, there were also mummy shaped coffins consisting of two equal parts. These had a shallow lower case and an upper lid, joined at the level of the mummy within. The back of the lower part sometimes projects slightly. A third type

is a rectangular coffin with a vaulted roof and four posts in the corners. There was a rich variety of iconography that accompanied these various coffins.

Further variations can be found from the volatile times of the 8th and 7th centuries BC. However, there was also apparently a lack of skilled craftsmen which resulted in the widespread production of crude coffins, particularly in Middle Egypt and the Memphis area.

Then the Nubian period, particularly during the reign of Taharqa, produced a period of stability. Typical fine coffins of this period might include an inner coffin in mummiform with a foot pedestal. On the lid, below the winged Nut figure on the breast might appear scenes of judgment and the mummy on its bier. Typically, small figures of protective deities might adorn both sides of the lid.

The inside of the coffin often contained excerpts from the Book of the Dead, usually accompanied by the figure of Nut. The outer coffin of the typical 25th Dynasty was decorated with solar scenes on its vaulted roof and the Four Sons of Horus on the side walls. On its roof was a recumbent Anubis, while small figures of falcons surmount the posts. While few royal coffins of this period are known, the falcon headed silver coffin of Sheshonq II is exceptional.

During the Late Period, from about the 26th Dynasty and later, wooden coffins have similar shapes. The flat lower part of the coffin serves merely as a support, not a container for the mummy, because it is was now covered by a much more convex lid. Figural representations became less numerous, replaced either partially or completely by long tests. These were excerpts from the "Saite version" of the Book of the Dead, which were written on the lid in vertical columns. Some of the lids after the Saite period also have carved decorations.

By the end of the Pharaonic period, coffins and mummy containers varied considerably and were sometimes very specific to different locales, reflecting both the changing nature of Egyptian leadership, such as the Greeks, the inclusion and assimilation of foreign gods, as well as the diversity that was often found during the earlier intermediate periods.

References:

|

Title

|

Author

|

Date

|

Publisher

|

Reference Number

|

|

Ancient Gods Speak, The: A Guide to Egyptian Religion

|

Redford, Donald B.

|

2002

|

Oxford University Press

|

ISBN 0-19-515401-0

|

|

Art and History of Egypt

|

Carpiceci, Alberto Carlo

|

2001

|

Bonechi

|

ISBN 88-8029-086-x

|

|

Atlas of Ancient Egypt

|

Baines, John; Malek, Jaromir

|

1980

|

Les Livres De France

|

None Stated

|

|

Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, The

|

Wilkinson, Richard H.

|

2003

|

Thames & Hudson, LTD

|

ISBN 0-500-05120-8

|

|

Complete Valley of the Kings, The (Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs)

|

Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H.

|

1966

|

Thames and Hudson Ltd

|

IBSN 0-500-05080-5

|

|

Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, The

|

Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul

|

1995

|

Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers

|

ISBN 0-8109-3225-3

|

|

Egyptian Religion

|

Morenz, Siegfried

|

1973

|

Cornell University Press

|

ISBN 0-8014-8029-9

|

|

Egyptian Treasures from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo

|

Tiradritti, Francesco, Editor

|

1999

|

Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

|

ISBN 0-8109-3276-8

|

|

Guide to the Valley of the Kings

|

Siliotti, Alberto

|

1997

|

Barnes & Noble Books

|

ISBN 0-7607-0483-x

|

|

Life of the Ancient Egyptians

|

Strouhal, Eugen

|

1992

|

University of Oklahoma Press

|

ISBN 0-8061-2475-x

|

|

Mummies Myth and Magic

|

El Mahdy, Christine

|

1989

|

Thames and Hudson Ltd

|

ISBN 0-500-27579-3

|

|

Mummy, The (A Handbook of Egyptian Funerary Archaeology)

|

Budge, E. A. Wallis

|

1989

|

Dover Publications, Inc.

|

ISBN 0-486-25928-5

|

|

Quest for Immortality, The: Treasures of Ancient Egypt

|

Hornung, Erik & Bryan, Betsy M., Editors

|

2002

|

National Gallery of Art

|

ISBN 3-7913-2735-6

|

|

Tutankhamun (His Tomb and Its Treasures)

|

Edwards, I. E. S.

|

1977

|

Metropolitan Museum of Art; Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

|

ISBN 0-394-41170-6

|

|