The Mawlawi Museum and Sunqur Sa'di Madrasa

by Lara Iskander

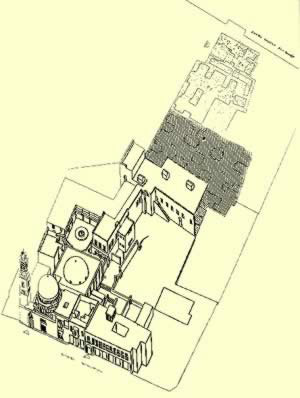

The Mawlawi Museum in Cairo, along with the monumental presence of the Sunqur Sadi Madrasa and the other archeological remains exhibited in the restored area of Shari Al-Siyufiyah are part of a great Complex which also includes the Sadaqa Mausoleum and the Yeshbak Palace.

The Mawlawi Complex has a great historical significance not only because it witnessed the end of the Mawlawi Sect, but also for its unique presence in Egypt as the only SamaKhana (hall) where the Mawlawi Dervishes preformed their rituals. The Museum lies in a very popular area- near the Qalaa (Citadel)- between two narrow streets, Manah Al-Waqf and Es-Siyufiyah

Main Entrance to the Mawlawi Complex

The Mawlawi Dervishes (16th-20th centuries)

The order of the Mawlawi dervishes, commonly known as the "Whirling Dervishes" fraternity of Sufis (Muslim mystics) was founded in Konya, Turkey, by the Persian Sufi poet Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi (1273), whose popular title Mawlana ("our master") gave the order its name. Along with the Ottoman expansion, this order spread through the Islamic world with many centers connected with the Mother House in Konya. The order moved from Konya to Aleppo, Syria in 1925, then to Damascus, and in 1929 the Mawlawi Order came to Cairo and settled in the area at the foot of the Citadel near the Sultan Hassan Mosque.

The Sama Khana, part of the Mawlawi Complex located in Islamic Cairo, has been restored and inaugurated through the combined efforts of Professor Guiseppe Fanfoni and by the Italian-Egyptian Center for Professional Training in the Field of Restoration and Archeology.

The Sama'Khana dome with the Mausoleum at the back

The dome of Sadaqa Mausoleum seen from Shari-Es-Siyufiah

The Madrasa of Sunqur Sadi (14th century)

Sunqur Sadi lived during the Sultan al-Nasir Mohammed Ibn Qalaun, in a period of particular wealth for Egypt. Prince Sunqur Sadi is known to have built several monumental buildings.

Above: The excavated area of the Madrasa on the lower floor of the Sama'Khana

Prince Shams Al-Din Sunqur Sadi constructed this Madrasa in Shari Es-Siyufiyah (Siyufiyah Street), outside Cairo town walls. He considered this architectural work the most important of his life.

The magnificence of his palace presents architectural aspects similar to those of the Bashtak Palace and is considered to be one of the most impressive Mamluk buildings in Cairo, even if it is reduced to ruins today.

Despite of its huge walls, the palace is somewhat hidden due to the presence of several buildings surrounding it. Its great faade is revealed as you enter through the Complex courtyard. It is understood that this palace was built in several stages. In 1476, the palace was enlarged by Yashbak. He added a monumental entrance, large and majestic with beautiful sculpted decorations "Mukkarnas". After his death the property passed on to Aqbardi.

Unfortunately, due to the weak state of the palace, its not possible to visit the inside nowadays.

The Mawlawis of Shari Es-Siyufiyah

The entire area of the Palace including the Sunqur Sadi Complex passed to the Mawlawi Dervishes Order in 1607.

The architectural Mawlawi complex, developed in the area between the remains of Sunqur Sadi Madrasa and Yashbak Palace using suitable pre-existing monuments and adapted them to their new functions. The Mawlawis -inspired by the plan and architecture of the Mother House in Konya- built a new wing along Shari Es-Siyufiyah giving a direct entrance from the street to the complex.

Entrance to the Sama'Khana Hall

The SamaKhana

The Cairo SamaKhana was one of the latest to be built during the long period of the existence of the Mawlawi community.

The word Sama in Arabic means listening, which was a "Sufi" (Muslim Mystic) practice of listening to music and chanting to be drawn closer to God. The Mawlawi Dervishes combined Sama with dancing.

Some of them even requested that there should be no mourning at their funeral, insisting instead that the Sama sessions be held to celebrate their entrance into eternal life.

The Cairo SamaKhana was also the last to remain active after the edict that closed the Tekkiya (the dance Hall) and the dissolution of the Dervishes Turkish confraternities by Ataturk in 1925. The Cairo Mawlawi group was also dissolved in 1945 and the whole complex was abandoned.

The Museum now exhibits the photographs of the Mawlawis as well as some documents. Some show-windows set up in this area exhibit archeological findings of the remains of the Madrasa. There are also two other windows in the great "Iwan", one of which exhibits the "Mensnevi" book written by Jala Al-Din Rumi donated to the Italian Centre by the Turkish Ministry of Culture during the ceremony held in the Sama Khana on January 18th, 1998. The other shows a Mawlawi dress donated by "Istanbul Sama group" during the Sama that took place on June 30th, 1998.

Top: Ceiling and Qu'ranic inscriptions of the Iwan

View of the Madrasa's restored Iwan where the Mawlawi dress is exhibited

Symbolism of the Mawlawi robes and dancing

The dervishes wear over all other garments a black robe (khirqah), which symbolizes the grave, and the tall camel's hair hat (sikke) represents the headstone. Underneath are the white dancing robes consisting of a very wide, pleated frock (tannur), over which fits a short jacket (destegl). On arising to participate in the ritual dance, the dervish casts off the blackness of the grave and appears radiant in the white shroud of resurrection. The head of the order wears a green scarf of office wound around the base of his sikke.

The Dervish dance was an outstanding example of pure dance. The procedure is part of a Muslim ceremony called the" Zikr" of which the purpose is to glorify God and seek spiritual perfection. The dance area is circular and everything is according to a central plan symbolizing the Universe. The philosophical meaning of the spinning movement is based on the idea that the world begins at a certain point and ends at the same point; therefore the dervishes sit in a circle listening to music. Then, rising slowly, they move to greet the sheikh or Mawlana (master), and cast off the black coat to emerge in white shirts and waistcoats. They keep their individual places with respect to one another and begin to revolve rhythmically. They throw back their heads and raise the palms of their right hands, keeping their left hands down, a symbol of giving and taking and the link between the earth and heavens. The rhythm accelerates, and they whirl faster and faster. In this way they enter a trance in an attempt to lose their personal identities and to attain union with the Almighty. Later they may sit, pray, and begin all over again. The ceremony always ends with a prayer and a procession.

The Dervish dance also happens to be the origin of another folkloric dance, which is very common in Egypt, called "Tanoura dance". Though very similar to the Mawlawi dance, it does not share the same beliefs and religious rituals, as it is only considered an entertainment. Twisting and turning, the multicolored dress of the dervish creates the illusion of a human kaleidoscope. These dancers wear a more colorful outfit and are mostly seen during the "Mooled", festivities that take place in Islamic Cairo and lately in worldwide Cultural Events and festivals.

See also:

References: