Restoring Egyptian Monuments

by Jimmy Dunn writing as Mark Walters

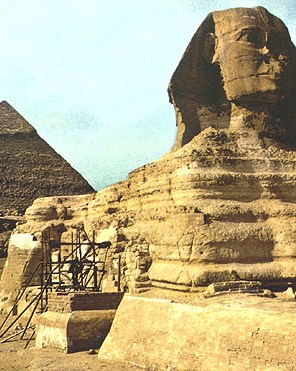

Sometimes there have been complaints about restoration work carried out in Egypt, a situation which is easy to criticizes, but much more difficult to find equitable solutions. Egypt has thousands of historical monuments, yet it does not have the resources of many western nations. Also, so many of the monuments are thousands of years older then those found in the west, and that creates complexities that few really understand. For example, consider that many monuments were built from the stones of even more ancient monuments, and perhaps have been restored even in ancient times.

Restoration of a monument therefore does not simply imply patching or rebuilding a wall here, or a column there. Certainly there are times when a monument is not completely restored. But in order to effect a good restoration the monument must be taken apart stone by stone in order to understand the circumstances in which it was constructed. Moreover, individual building blocks must often be studied, as it is possible that they originated from another building, and sometimes may shed considerable light on Egypt's antiquities. Occasionally, writing is found when restoring buildings that was not otherwise visible, and which might lead to new, major archeological discoveries.

For example, when Karnak's ninth pylon was restored, many of the blocks and stones discovered in the foundation were found to have come from buildings dated from the Amarnian period. This was an interesting time in ancient Egypt, and because of the radicalism of Akenaten, many if not most of his monuments were destroyed by later Egyptian pharaohs. Yet in this restoration process, some twelve thousand stones of that period were found, many with well preserved carved and painted decorations that shed much light on the Amarnian period.

Yet again in restoration work at Karnak, blocks from an earlier chapel were found in the foundation of the third pylon. After paper analysis, called anastylosis, architect Henri Chevrier was able to piece together the 12th Dynasty "White" Chapel of Senwosret I.

Prior to any restoration, architects must systematically photograph and create graphic surveys of the entire structure to be restored. This might even include the surrounding area, as some parts of the monument may have already collapsed. The monument is then disassembled, beginning at the top. Each piece removed is numbered, photographed and recorded. including those that may have been found in the immediate vicinity of the monument, if collapse has occurred. These are then stored in what is sometimes called a "stone museum".

Frequently, due to Egypt's high underground water level, building blocks must be repaired. Some of the sandstone and limestone contains high levels of sea salt. When the stones come into contact with dampness, they become unstable as the salt crystals migrate to the surface of the stone. This causes the outer surface of the stone to crumble. Ethyl Silicate is often used to repair these stones, but often the building blocks are beyond repair, and must be replaced with new blocks. Often there are many stone fragments where collapse has occurred, so these are collected and pieced back together if possible.

Once the disassembly and repair work has been completed, the monument is reassembled. There is actually a convention known as the Charter of Venice that dictates how this is to be done. Basically, it calls for the building to be reassembled respecting all changes that have occurred to it over history. Where needed, such as in foundations, new stones that are carefully crafted to reflect the old ruined stones may be used.

At this stage, statues that were possibly removed are returned and cleaned, often using pressurized water and sand. Broken shards of statues may be found, and reattached to the statues. Finally, wall paintings may be restored and preserved using micro-abrasion for cleaning whereupon a chemical fixative will be sprayed.

This is certainly an oversimplification of the process of monument restoration, but when one considers the thousands of ancient Pharaonic, Christian and Muslim monuments in Egypt, the obvious becomes clear. The Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) do their best with the limited resources available to them.

See Also:

Life in Ancient Egypt

Last Updated: August 8th, 2011