Senusret III, the 5th King of the 12th Dynasty

by Jimmy Dunn

Senusret III is probably the best attested king of the New Kingdom. He ruled the country for perhaps as long as 37 years as the 5th pharaoh of Egypt's 12th Dynasty from around 1878 until 1841 BC. He is probably also the best known of the Middle Kingdom pharaohs to the public because of his many naturalistic statues showing a man with often heavy eye-lids and lined continence. Later statues seem to portray him with increasing "world-weariness". Taken along with contemporary text, these statues seem to wish us to believe Senusret III was a king possessed of a concerned, serious and thoughtful regard for his high office.

Egyptologists make a great deal out of Senusret III's statuary. It is much loser in terms of the rigid ideological representations of earlier kings and illustrates a shift in both the function of art and a change in the ideology surrounding the king. The human qualities of the statues give a sense of age and tension, rather than the all powerful king portrayed in older works. We see in these statues a shift away from the king as god, and more towards the king as leader.

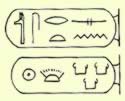

Senusret was this king's birth name, which mean, "Man of Goddess Wosret". He is also sometimes referred to as Senwosret III and Senusert III, or by the Greeks, Sesostris III. His throne name was Kha-khau-re, meaning "Appearing like the Souls of Re". Senusret III was most surely the son of Senusret II, changing a trend of having alternate leaders named Senusret and Amenemhet. We know of no co-regency with his father, though most of the previous 12th Dynasty kings shared at least a few years of their reign with their sons, and a co-regency would clear up some questions about Senusret III's long reign. His mother may have been Khnumetneferhedjetweret (Khanumet, Weret), who we believe was buried in a tomb near his pyramid at Dahshur. He was married to a principle queen named Mereret, who probably outlived him, and may have also been married to his sister, Sit-Hathor. His son and successor was Amenemhet III.

Senusret III must have been a very dominant figure within his time. Manetho describes him as a great warrior, not surprisingly, because he also says he was "of great height at 4 cubits, 3 palms and 2 fingers" (over 6 ft, 6 in or 2 meters). In addition, he may also have been the model for the Sesostris of Maetho and Herodotus, who was probably a composite, heroic Middle Kingdom ruler who was suppose to be a model for future kings.

While there had been fortifications built in Nubia, Amenemhet II and Senusret II, Senusret III's predecessors, had not been extremely active in Nubia militarily, and some Nubian groups had gradually moved north past the Third Cataract. Senusret III initiated a series of devastating campaigns in Nubia very early in his reign (perhaps year 6) in order to secure his southern borders and protect the trading routes and mineral resources. Apparently, the Nubians were a troublesome lot during his reign, for Senusret III would again have to mount campaigns in at least the years 8, 10, 16 and 19 of his reign. Regardless, these campaigns seem to have been for the most part successful, for the king had inscribed on a great stele at Semna erected in year 8 of his rule, now in Berlin, "I carried off their women, I carried off their subjects, went forth to their wells, smote their bulls; I reaped their grain, and set fire thereto". In other words, he killed their men, enslaved their women and children, burnt their crops and poisoned their wells. The stele also provides that no Nubians were allowed to take their herds or boats to the north of the specified border.

Fortification at Buhen

To facilitate these military actions in Nubia, he had a an existing bypass canal around the First Cataract (rapids) at Aswan, originally dug in the Old Kingdom by Merenre (or Pepi I) cleared, broadened and deepened. According to an inscription, he had it repaired again in year eight of his reign. This canal was near the island of Sehel.

His predecessors had also established a policy of building fortresses in Nubia, but in order to further secure the area, Senusret III built more fortresses than any of the the other Middle Kingdom rulers. In the 64 km (40 mile) length of the Second Cataract in Lower (northern) Nubia there were no less than eight such fortresses between Semna and Buhen However, many Egyptologists disagree with exactly how many of these fortresses were built by Senusret III, or were instead, simply rededicated or enlarged.. These fortresses were in close contact with each other, and with the region's vizier, reporting the slightest movements of Nubians. At least some of the fortresses appear also to have been specialized. For example, the one at Mirgissa was more involved with trade, whereas others, such as the fortress at Askut, were used as supply depots for campaigns into Upper (southern) Nubia.

Senusret III managed to expand Egypt's boarders further south than anyone ruler before him, of which he was proud. A stele at Semna with a duplicate at Uronarti records:

"I have made my boundary further south than my fathers,

I have added to what was bequeathed me.

I am a king who speaks and acts,

What my heart plans is done by my arm.

One who attacks to conquer, who is swift to succeed,

ln whose heart a plan does not slumber.

Considerate to clients, steady in mercy,

Merciless to the foe who attacks him.

One who attacks him who would attack,

Who stops when one stops,

Who replies to a matter as befits it.

To stop when attacked is to make bold the foe's heart,

Attack is valor, retreat is cowardice,

A coward is he who is driven from his border.

Since the Nubian listens to the word of mouth,

To answer him is to make him retreat.

Attack him, he will turn his back,

Retreat, he will start attacking.

They are not people one respects,

They are wretches, craven-hearted.

My majesty has seen it, it is not an untruth.

I have captured their women,

I have carried off their subjects,

Went to their wells, killed their cattle,

Cut down their grain, set fire to it.

As my father lives for me, I speak the truth!

It is no boast that comes from my mouth."

In fact, he not only stabilized Egypt's southern border at Semna, his troops regularly penetrated the area beyond and we know of a record recording the height of the inundation as far south as Dal, many miles beyond Semna. This stele continues with an admonishes later kings,

"Now as for every son of mine who shall maintain this boundary, which My Majesty has made, he is my son, he is born of My Majesty, the likeness of a son who is the champion of his father, who maintains the boundary of him that begat him. Now, as for him who shall relax it, and shall not fight for it; he is not my son, he is not born to me."

Certainly his son, Amenemhet III heeded this warning, and interestingly, Senusret III was later deified in Nubia as a god. However, we also know that, in what we believe to be his final campaign in Nubia in year 19 of his reign, his efforts were less successful. Apparently, due to a drop in the Nile's water level, his forces had to make a retreat to avoid being trapped.

Senusret III Stele from Aswan

Most of Senusret III's military attention was directed towards Nubia, but he is also noted for a campaign in Syria against the Mentjiu, where rather than a goal of expansion, he seems to have been after retribution and plunder. We owe this information to a a stele belonging to an individual named Sobkkhu, who apparently also participated in the Nubian campaigns. The king apparently led this campaign himself, capturing the town of Sekmem, which may have been Shechem in the Mount Ephrain region.

It was probably during Senusret III's reign that we also find the "Execration Texts". These were inscriptions found in Nubia and Egypt, usually inscribed either on magical figurines or on pottery. The inscriptions were usually a list of enemies of Egypt. These objects were often ritualistically smashed, and the shards placed under the foundations of new building, thus "smothered", or nailed at the edge of the area they were meant to protect.

The plunder from the Nubian and Syrian campaigns was mostly directed towards the temples in Egypt, and their renewal. For example, at Abydos, an inscription by a local official named Ikhernofret states that the king commissioned him to refurbish Osiris's barge, shrine and chapels with gold, electrum, lapis lazuli, malachite and other costly stones. He also adorned the temple of Mentuhotep II at Deir el-Bahari (West Bank at Luxor) with a series of six life size granite standing statues of himself wearing the nemes headdress. They once lined the lower terrace.

Religiously, we are told in a graffiti that, even though his capital, burial ground and other interests were in Northern Egypt, he also helped maintain a large number of priests associated with the cult of Amun in Upper (southern) Egypt at Thebes. He also had built a large temple to the old Theban war god, Montu, just north of Karnak at Nag-el-Medamoud. While this temple was refurbished in the New Kingdom and again in the Greek and Roman period, nothing remains of it save two finely carved granite gateways that were discovered in 1920, along with some very splendid statues and a few inscriptions.

Domestically, Senusret III was able to carry on his military campaigns and building projects because he had matters at home largely under control. He divided the country into three administrative divisions (waret), including a North, South and the Head of the South (Elephantine and Lower Nubia), that were each administered by a council (djadjat) of senior staff who in turn reported to a vizier. This sufficiently weakened the power of local nomarchs (governors) and other high officials who had once again begun to challenge the central government and the monarch. Decentralization due to powerful local officials and nobles had, in the past, created chaos and ultimately led to the dark times of the First Intermediate Period. It would seem that most all of the Middle Kingdom rulers were aware of this threat, and were constantly on guard.

This new administrative scheme apparently also had another effect, in that it promoted the rise of the middle class, many of whom were incorporated into the administration, and were no longer under the influence and control of the local nobles.

Sunusret III had his pyramid built at Dahshur, a mostly Middle Kingdom necropolis. It was the largest of the 12th Dynasty pyramids, but like the others with mudbrick cores, after the casing was removed it deteriorated badly. In the excavation season of 1894-1895, Jacques de Morgan also found the tombs of Queen Mereret and princess Sit-Hathor near the northern enclosure wall of Senusret III's pyramid complex. Also found with these tombs were some fine jewelry, missed by earlier robbers. However, some Egyptologists doubt that Senusret III was buried in this pyramid. He also had an elaborate tomb and complex built in South Abydos. This huge complex stretches over a kilometer between the edge of the Nile floodplain and the foot of the high desert cliffs that form the western boundary of the valley. This complex consists of an underground tomb which, at least at one time, was considered to be the largest in Egypt (that may have been eclipsed by the discovery of the Tomb of Ramesses II's Sons in the Valley of the Kings). Other components include a mortuary temple at the edge of the cultivated fields and a town south of the tomb that supported the complex. The name of this funerary complex was "Enduring are the Places of Khakaure Justified in Abydos".

Senusret III is further attested by blocks from a doorway found near Qantir and by his rock inscriptions near the island of Sehel south of Aswan that record the reopening of the bypass canal.

Reference:

|

Title |

Author |

Date |

Publisher |

Reference Number |

|

Chronicle of the Pharaohs (The Reign-By-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt) |

Clayton, Peter A. |

1994 |

Thames and Hudson Ltd |

ISBN 0-500-05074-0 |

|

Complete Valley of the Kings, The (Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs) |

Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. |

1966 |

Thames and Hudson Ltd |

IBSN 0-500-05080-5 |

|

History of Ancient Egypt, A |

Grimal, Nicolas |

1988 |

Blackwell |

None Stated |

|

Monarchs of the Nile |

Dodson, Aidan |

1995 |

Rubicon Press |

ISBN 0-948695-20-x |

|

Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, The |

Shaw, Ian |

2000 |

Oxford University Press |

ISBN 0-19-815034-2 |

Last Updated: June 20th, 2011