The Amarna Period

by Jimmy Dunn

The Amarna Period in Egyptian history is a spectacular time filled with mystery, regardless of the massive research and analysis of Egyptologists and layman enthusiasts. Because religion played such a significant role in all of Egypt's history, the period becomes a grand anomaly worthy of such focus. Most of the research and excavations surrounding this period focus on five areas. These areas include the main players during the period, who are certainly not limited to Akhenaten and Nefertiti, the city founded by Akhenaten from which the period derives its name, the religion of the period, the art of the period and the period's literature (specifically correspondence known as the Amarna Letters).

In a very strict sense, the Amarna Period might be considered to encompass only the reign of Akhenaten. He founded the city we most frequently refer to as Amarna (ancient Akhetaten), which hardly lasted beyond his reign. However, Egyptologists and others usually expand this period to include at least the latter part of his father, Amenhotep III's reign through or at least into the reign of Tutankhamun. The ancient Egyptians themselves actually appear to consider this period to run through the end of the 18th Dynasty and the reign of Horemheb, though clearly the latter kings of this dynasty sought to return Egypt to its traditional religion.

The primary reason that most sources begin the Amarna period with the latter part of Amenhotep III's reign is probably due to the fact that this was the period when Akhenaten, originally Amenhotep (IV), rose to crown prince and was subjected to the influences that would eventually cause him to attempt to altar Egyptian religion. He may have even served as a co-regent to his father. However, it should be noted that the Akhenaten's father and grandfather both venerated the god Aten, though certainly not in the radical method of their offspring. The end of this period is marked by the efforts of the real powers behind the reign of Tutankhamun, consisting of Ay and Horemheb, working to restore the traditional Egyptian religion, though such efforts may have been made even as early as the latter years of Akhenaten's reign. However, there is reason to believe, due to the omission of Ay's and Horemheb's names form certain kings lists, that the ruler of the 19th Dynasty included them in the Akhenaten heresy.

What of course sets this period apart from the remainder of Egyptian history is first and foremost, its religious theology, together with a distinct form of art.

The sun god and the king lay at the heart of Egypt's theology as it developed over the previous centuries. It was the daily course of the sun god, who was also the primeval creator god, that guaranteed the continued existence of his creation. The sun god's daily journey through the heavens was symbolically enacted in temples with the principle aim of maintaining the created order of the universe. The king partook a crucial role in this daily event, at least symbolically through the god's priests.

Re, the sun god, went through a daily cycle of death and rebirth, dying at the end of each day and being reborn in the morning as Re-Horakhty, and it was through this cycle that the blessed dead traveled so as to enjoy rebirth along with the sun. Osiris, the god of the dead and the underworld, with whom the deceased were traditionally identified, was increasingly seen as an aspect of Re, and the same held true for all other gods.

Hence, towards the end of the reign of Amenhotep III, the cult of many gods were increasingly solarized, though the king attempted to counterbalance this development by commissioning an enormous number of statues of a multitude of deities and by developing the cult of their earthly manifestations. However, even by the end of his reign, the hymns devoted to the sun god clearly set him apart from other deities. His successor, though, would revolutionize the worship of the sun.

Traditionally, the sky-god Horus had been incarnate in the king and carried the Aten, the disk of the daytime sun named Re, across the heavens upon giant falcon wings. In the final stage of Akhenaten's revisions, the falcon of Re-Horakhty was transformed from the bearer of the solar disk upon its vertex into the disk itself. Hence, though the sun disk had been there all along, its nature was completely changed during the reign of Akhenaten.

It has always been difficult to comprehend the essential features of this revolution in religion because, as is becoming ever more clear, it expressed itself for the most part in conventional forms. The language in the hymns of Akhenaten to Aten parallel, more or less word for word earlier religious texts, as did some of the customs surrounding Aten's worship. Even motifs of Amarna art, such as the disk with rays or the prostrate figures of the subjects, had existed for a long time, at least as literary images. In fact, Erik Hornung tells us in his Conceptions of God in ancient Egypt that the real revolution involved:

"...the implied transformation of thought patterns, in which all the traditional forms were bathed in the glare of a new light which the Egyptians came to find intolerable. Beginning with the change in the king's birth name, from which the name of the (state god) Amun was removed, there was a step-by-step process of elimination. Amun was replaced by Aten, mythical statement by rational statement, many-valued logic by two-valued logic, the gods by God. All this was accomplished according to a well-conceived plan."

Of course, a part of the resistance to Akhenaten's religion must have been the displacement and significant reduction in status of the powerful priests of Amun and other gods.

Erik Hornung explains that Akhenaten was not a visionary but rather a methodical rationalist. He was a worldly philosopher who took the throne of perhaps the most power empire on earth at that time, and implemented reforms one by one as soon as the necessary political conditions had been created. He manipulated the power of the priestly institutions at his command very brilliantly.

For example, in the fourth year of his reign, during an important initial phase of this religious revolution, the high priest of Amun was sent on a quarrying expedition very literally into the wilderness. He was therefore removed from events in the capital of Thebes, where Amun was replaced by Aten as the head of the pantheon, and a series of temples were dedicated to the new state god at Karnak.

According to Norman de G. Davies and Hanns Stock, these initial steps do not appear to damage the traditional structure of henotheism, a religious concept regarding the worship of several divinities independently. Hence, at the time these temples were being built in Thebes which was a year prior to Akhenaten changing his name from Amenhotep IV, he assigned a favored position beside Aten to the ancient solar deities Re, Horakhty and Shu. On a private stela of this period Horakhty is even said to be "the god like whom there is no other". This did not belittle Aten, but singles out the god who is being addressed, very much in the spirit of earlier henotheistic worship.

Even Syncretism remained alive. Horakhty and Aten were combined in the hawk-headed figure of Re-Horakhty-Aten, and Re-Horakhty was placed at the head of the earlier royal titulary that was established for the god Aten as ruler of the world. Erik Hornung tells us that:

"...in the early years of the reign the complementary status of god and gods was not attacked, but the hitherto vast range of the pantheon was restricted in unprecedented fashion to its solar aspect. The dark world of the gods of the dead, Osiris and Sokar, was drawn into the light of the sun god, and finally banished completely from the image of the cosmos."

However, this transformation seems not to have been caused by an evolution in the king's ideas, but rather a carefully thought out process made by a man who's religious theology was already developed. Neither was his ideas implemented without an understanding of the real world.

At some point we know between Akhenaten's sixth and ninth year as king, his program of religious reform reached its goal. In order to fully escape the domain of Amun, he had built his new capital city and now, the Aten received a new titulary in which even Horakhty (Horus of the horizon) no longer appeared. His name was replaced with the new phrase, "horizon-ruler". The deity was no longer represented in the hawk form, which was one of the oldest manifestations of the sun god, though the hawk, as well as the uraeus snake continued as two of the few divine animals that were tolerated at Amarna.

For the first time in history, the divine had become one, though with a complementary multiplicity so that the mass of divine forms was reduced to the single manifestation of the Aten. Now, all that is left is a double name, that of Re, who reveals himself (has come) as Aten. With this change, the king also became the "sole king like Aten; there is no other great one except him". To at least Akhenaten, now, there was but one god.

Essentially, anything that does not fit into the nature of the Aten was no longer divine. The main difference between the hymns of Akhenaten, though using similar working to earlier works, is what they omit. For example, now, the difference between night and day is simply that during the night, the Aten is not present. No longer do other gods rule the dark. Furthermore, several thousand years of myths can no longer exist. The Aten's nature is not revealed but is only accessible through intellectual effort and insight only to Akenaten and those whom he teaches. Akenaten tells us that "there is no one else who knows you (the Aten)", and he is constantly given the epithet Waenre "the unique one of Re".

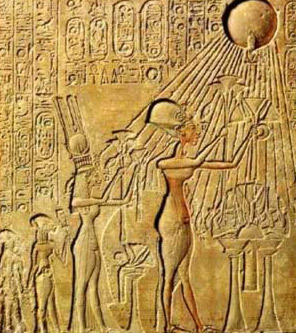

Hence, the Aten is so far removed that an intermediary is required in order to be accessible to mankind, and that intermediary is the king. During the New Kingdom, the use of intermediaries had been increasingly important to access the gods. However, worshipers had been able to turn to a variety of these, including sacred animals, statues, dead men who had been deified who functioned in this capacity. Now, there only recourse was the king, who becomes the sole prophet of their god. Hence, the faithful of the Amarna period pray at home in front of an altar that contains a picture of the king and his family. The new religion could be summed up as "there is no god but Aten, and Akhenaten is his prophet".

Before Akhenaten, the placing of one god in a privileged position never threatened the existence of the remaining gods. The one and the many had been treated as complementary throughout Egyptian history and gods were not mutually exclusive. Now they were and we witness the formulation of a new logic. Although his qualities are not absolute, the Aten becomes a monotheistic God by virtue of this. He becomes a jealous god, who will tolerate no other gods before him.

Hence, the transformation becomes visibly apparent because of the unparalleled persecution of traditional gods, above all, Amun. Akhenaten's stonemasons swarm the country and even abroad to remove the name of Amun from all accessible monuments, including even the tips of obelisks, under the gilding on columns and in the letters of the achieves. In fact, Egyptologists use these erasures and later restorations of the name of Amun in order to date monuments to the period before Amarna. Though Amun felt the worst of Akhenaten's revolution, other gods were also eliminated.

Akhenaten's religion did not outlive him, though for a few years the Aten remained the leading god and its name was never persecuted. Significantly, after his death the old gods were first restored, decades before Akhenaten's personal memory was attacked. The traditional religion was needed to once again balance Ma'at.

One must remember that it was Akhenaten's religion. Though the king's religion may have been the official theology of the ancient country, obviously that of Akhenaten never completely took hold in Egypt, and hence, the old religion certainly never completely disappeared during his reign. He may have eradicated the names of other gods, but he could not extinguish several thousand years of mythological traditions, particularly at a time when Egyptian religion was increasingly democratized. Egyptian religion had always been, at least to some extent, been a divided process between the state religious institutions and the common people and obviously there was resistance to Akhenaten's theology on both levels. The state institutions were directly effected, but trouble from that sector seems to have been brewing all along during his reign. One wonders whether the true belief of the common people, particularly outside of his new capital, ever changed extensively outside of their participation in official festivals. In fact, even at Amarna itself there are a fair number of surviving votive objects, stelae and wall paintings that depict or mention gods such as Bes and Taweret (both connected with childbirth; the harvest-goddess Renenutet; the protective deities Isis and Shed; Thoth (the god of scribes; Khnum, Satet and Anuket (the triad of Elephantine); Ptah of Memphis and even Amun of Thebes.

What is evident is that most of the attributes we can assign to this period revolved around Akhenaten's religion. This includes the moving of the capital to the area we call Amarna, which may have not only been an effort to escape Amun dominated Thebes, but also to allow an island of religious revolution within what was a very traditional country. Akhenaten may very well have needed this support center where, at least in one geographic location, his religion could flourish without the pressure of the established temple communities. In establishing the capital, speed became a determining factor of new building technique. Though the earliest structures of Amenhotep IV employed the traditional large sandstone blocks commonly used for temple walls, at Amarna and Thebes buildings began to be built with smaller blocks known as talatat. One person could handle these blocks and this made it easier to erect large buildings in a relatively short period of time. However, like Akhenaten's religion, after the Amarna period this method was abandoned, perhaps because if was found that the smaller blocks needed a great deal for plaster finishing to close the gaps between individual stones, and therefore the reliefs inscribed on these walls could not withstand the test of time.

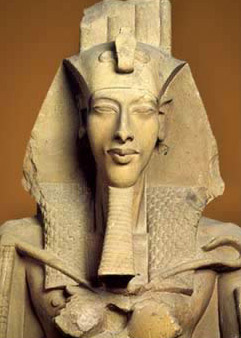

Akhenaten's religion also effected the Art of Egypt during the Amarna period. The art of this period may, in fact, have been the most important and lasting change. In certain respects, there was a modification of Egyptian art that was no less revolutionary than Akhenaten's religion. In the earliest representations of Amenhotep IV (later changed to Akhenaten), he is shown in a traditional style closely resembling the one used to portray both Tuthmosis IV and Amenhotep III. However, not long after his accession, Amenhotep IV had himself depicted with a thin, drawn out face with pointed chin and thick lips, an elongated neck, almost feminine breasts, a round, protruding belly, wide hips, fat thighs and thin, spindly legs. This style was somewhat restrained at first, but on most of the Theban monuments and during the early years at Amarna the king's features became so exaggerated that his representations more resembled a caricature. This style was not only used to depict the king, but also his family and all other humans as well, though usually in a less exaggerated form.

Like the revolution in religion, the art styles established during the Amarna period are no less controversial. Many Egyptologists believe that the extraordinary manner in which Akhenaten portrayed himself, his family and, to a lesser extent, all other human beings, somehow reflects the king's actual physical appearance, though perhaps in an exaggerated from that has been called 'expressionist' and even 'surrealist', and we are told by the king himself that it was he who instructed his artists in this new style.

Some of those who believe that the art portrays the king in a more or less a true form believe that he may have suffered from some disease or deformity and there has been much speculation on this as well. A number of pathologies have been suggested, including such conditions a Frohlich's Syndrom, which creates an appearance similar to that of Akhenaten in art.

However, others believe that the Amarna period art is more stylistic and symbolic, perhaps reflecting a feminine aspect of the Egyptian court. That the grotesque aspect of Akhenaten's portrayals owes more to artistic expression than to pathological considerations is suggested by the art style during his later years. Models and sketches found in he sculptors' studios at Amarna lack the exaggeration of the earlier style. In fact, some tomb scenes were even modified to mitigate the extreme style of the earlier carvings. One should also remember that in many of the depictions that were so exaggerated, Nefertiti did not at all resemble her beautiful bust now in the Berlin Museum, but was represented not unlike her husband.

Akhenaten in an exaggerated form;

Nefertiti in a form less attractive then her Berlin Bust

Nevertheless, not only the human figure was affected by this new style, but also the way they interact. Scenes of the royal family display an intimacy that had never before been shown in Egyptian art even among private individuals. Another characteristic feature of the Amarna style is its extraordinary sense of movement and speed. There is a general 'looseness' and freedom of expression that was to have a lasting influence on Egyptian art for centuries after the Amarna Period had come to an end, so in reality, Akhenaten's art, if nothing else, became a lasting influence.

Many scholars see a certain detachment of the royal house from the affairs of state, though how much so is difficult to say. Apparently the standard bureaucracy of the Egyptian government continued its endeavors to run the country while the king courted his god. Cracks can be seen in the Egyptian empire as early as the latter years of Amenhotep III, and they became ever more evident during the reign of Akhenaten. Though little appears to have been done to enforce Egypt's foreign holdings, the civil and military authority was probably left to the authority of two strong characters, consisting of Ay, who held the title 'Father of God' and who may have been Akhenaten's father-in-law, and the general Horemheb. Both men would eventually become kings before the end of the 18th Dynasty, and Horemheb particularly would be instrumental in reversing the damage done to the Egyptian state religion.

At home the period seems to have been totally consumed by the religious revolution. Most of what we know about this period domestically revolves around this new theology. Likewise, though we have considerable correspondence on the matter of Egypt's foreign relations, little action seems to have been taken. There is the possibility of some police actions, but apparently no large scale military expeditions took place which seemingly resulted in a contraction of the empire abroad at the hands of foreign powers.

There is considerable confusion at the end of Akhenaten's reign. Nefertiti, Akhenaten's famous wife was apparently had a considerable influence of the events at Amarna, showing up in almost all reliefs depicting the king during his early reign. Though many Egyptologists believe that she may have died early, other believe that she may have, after a name change, actually served as a co-regent to her husband, and possibly have even succeeded him on the throne of Egypt. There is also speculation, though she seems to have been an intrigal part of his religious revolution, that if she indeed outlived her husband, she may have even taken a step back from her spouse's religion during her later years. Irregardless, by the time that Akhenaten's son, Tutankauman, ascended the throne forces in the form of Ay and Horemheb appear to have been almost at once set on returning the status quo to traditional Egyptian religion. A stele erected during that young king's reign, most likely actually commissioned by Ay, records such a restoration.

In conclusion, Egypt's ancient history spans a great period of time in which any number of religious ideas developed and flourished. Capitals were moved, artistic changes took place, but in all this development, there were few if any periods that would rival the revolution in so short a time frame of the Amarna period. Akhenaten turned Egyptian tradition upside down, but clearly, his changes were not welcomed by the ancient Egyptians and their rejection of his heresy, upon his death, was swift and complete.

References:

|

Title |

Author |

Date |

Publisher |

Reference Number |

|

Akhenaten: King of Egypt |

Aldred, Cyril |

1988 |

Thames and Hudson Ltd |

ISBN 0-500-27621-8 |

|

Amarna Letters |

Forbes, Dennis C. |

1991 |

KMT Communications |

ISBN 1-879388-03-0 |

|

Art and History of Egypt |

Carpiceci, Alberto Carlo |

2001 |

Bonechi |

ISBN 88-8029-086-x |

|

Chronicle of the Pharaohs (The Reign-By-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt) |

Clayton, Peter A. |

1994 |

Thames and Hudson Ltd |

ISBN 0-500-05074-0 |

|

Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many |

Hornung, Erik |

1971 |

Cornell University Press |

ISBN 0-8014-8384-0 |

|

Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, The |

Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul |

1995 |

Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers |

ISBN 0-8109-3225-3 |

|

Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, A |

Hart, George |

1986 |

Routledge |

ISBN 0-415-05909-7 |

|

Egyptian Religion |

Morenz, Siegfried |

1973 |

Cornell University Press |

ISBN 0-8014-8029-9 |

|

Egyptian Treasures from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo |

Tiradritti, Francesco, Editor |

1999 |

Harry N. Abrams, Inc. |

ISBN 0-8109-3276-8 |

|

History of Ancient Egypt, A |

Grimal, Nicolas |

1988 |

Blackwell |

None Stated |

|

Shaw, Ian |

2000 |

Oxford University Press |

ISBN 0-19-815034-2 |

|

|

Private Lives of the Pharaohs, The |

Tyldesley, Joyce |

2000 |

TV Books, L.L.C. |

ISBN 1-57500-154-3 |

|

Thebes in Egypt: A Guide to the Tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor |

Strudwick, Nigel & Helen |

1999 |

Cornell University Press |

ISBN 0 8014 8616 5 |

|

Tutankhamun (His Tomb and Its Treasures) |

Edwards, I. E. S. |

1977 |

Metropolitan Museum of Art; Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. |

ISBN 0-394-41170-6 |