The Monastery of al-Baramus (Deir al-Baramus, Monastery of the Romans) At Wadi al-Natrun

by Jimmy Dunn

Introduction and History

In the Wadi al-Natrun, certainly one of the most famous regions in Egypt associated with Christian monasteries, the northernmost of the four communities is that of the Monastery of al-Baramus. It is also sometimes called the Monastery of the Romans and is very probably the first monastery established in the Wadi al-Natrun. In fact, it is said to occupy the place where Macarius the Great settled in 340 (or as early as 330) when he devoted himself to monastic life. The modern name of the monastery (al-Baramus) is Arabic and is derived from the Coptic Christian Pa-Rameos, which means "that of the Romans". The origin of this name is certainly in dispute. The most widely held tradition concerns Maximus and Domitius, who Coptic texts and tradition holds as Roman saints as well as children (perhaps illegitimate) of the Roman emperor Valentinian (presumably Valentinian I (364-375 AD). They are said to have gone to Scetis (Wadi al-Natrun) during the days of St. Marcarius after having visited the Christian shrines of Nicea and Palestine. St. Marcarius tried to dissuade them from staying, but the "two little strangers" nevertheless established themselves in a cell. The older of the brothers is said to have attained perfection before his death, and only three days later, the other brother died.

It is said that when the desert fathers came to Saint Macarius, he used to take them to the cell of the two brothers and say to them, "Behold ye the martyrdom of these little strangers". A year after their death, Saint Macarius consecrated the cell by building a chapel and said, "Call this place the Cell of the Romans". However, some scholars maintain that it was Paphnutius, Marcarius's successor, who first called the chapel by this name.

Some believe that the "young strangers" received by Macarius and later on venerated by the monks of the Wadi were not necessarily of Roman origin. In this tradition, it is thought that the name of the monastery could be due to the fact that a Roman monk named Arsenius settled in Wadi al-Natran (Scetis) in 394 and became the abbot of the community. Still other traditions hold that Arsenius had been the tutor of Arcadius and Honorius, the emperor Theodosius' sons, who in their turn became emperors. According to this interpretation, this bit of history could have led to confusion and the identification of the two "young strangers" as Romans.

Today, this monastery is significant in that it was founded on a site in front (south) of the Old Baramus monastery, discovered by archaeologists in 1994, which some say was incorrectly known as "the Monastery of Moses the Black". Others believe that Deir Anba Musa al-Aswad, or the Monastery of Saint Moses the Black, under the leadership of St. Isidore the Hegumen, was the original name. The older monastery probably dates to as early as 340 AD. It should be noted that there exists some confusion in regard to the current monastery's history in relationship to the old monastery. It is very possible that both existed concurrently at some point, with the former monastery known as Deir al-Baramus, and the current monastery known as the Monastery of the Virgin of Baramus, Hence, the history we have of the modern monastery certain encompasses that of both.

All four of the monasteries in the Wadi al-Naturn suffered six sacks. These occurred in 407, 410, 444, 507, 817 and the last in the eleventh century(some scholars also reference sacks in 810 and 870, without mention of those in 444, 504, 817 or the eleventh century), though the most severe threat to the monastery came in the form of the Black Death in the fourteenth century, which was followed by a famine. Each time the communities were attacked, the monastic buildings were damaged, the churches plundered and the monks either slain or carried off as captives.

Abbot Arsenius himself witnessed the devastating raids of 407 and 410 at Deir al-Baramus and both times he managed to escape the carnage. After the first, he returned to rebuild the cells and other parts of the monastery that had been destroyed, but after the raid in 410, he retired to Troe, the Cairo neighborhood called Tura today, where he died. There, a monastery was later dedicated to his memory.

St. Moses the Black, so named because he was Ethiopian and therefore of dark skin, did indeed reside in this monastery and was martyred in the first raid of 407. Before becoming a monk and priest, he had led a criminal life, but later repented his life of wrongdoing and retired to the Wadi where the examples of Saints Macarius and Isidore led him to a high degree of asceticism and holiness. However, having foreseen the attack of the Massic Berber tribe, he is said to have urged his disciples to leave the community in order to take refuge in safer surroundings. He, together with seven other monks, remained in order to fulfil the words from the Gospel of Matthew (26:52), "All who take the sword will perish by the sword".

The monastery also had a number of important visitors from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. During the first half of the fifteenth century, the Arab historian al-Maqrizi visited the monastery and was responsible for identifying it as that of St. Moses the Black. At that time, he found it to have only a few monks. Other famous visitors included Coppin (1638), who described it as the "fourth monastery" in the desert of "St. Marcarius Bahr al-Malamah" (sea of reproaches). According to the monks of that time, this name came from a tradition that held that. They maintained that at one time, the sea still bathed the monastery walls, and when St. Macarius, having seen a pirate ship approaching, prayed to heaven for help. Suddenly, the waters withdrew and at the same time the pirates and their ship were turned to stone. When De Maillet also visited the monastery in 1692, he was told the same story. He therefore called this place in his description "Valley of Bahr bila Ma" (sea without water). Other famous visitors descended on the monastery, including Thevenot (1657), De Maillet (1692), Du Bernat (1710) Sicard (1712), Sonnini (1778), Lord Prudhoe (1828), Lord Curzon (1837), Tattam (1839), Tischendorf (1845), Jullien (1881) and Butler (1883). Information from them and a few other travelers provide that there were 712 monks who lived in seven monasteries in this region, including twenty monks at the Monastery of al-Baramus in 1088, twelve monks in 1712, nine in 1799, seven in 1842, thirty in 1905, thirty-five in 1937, twenty in 1960 and forty-six in 1970. Today, the monastery is inhabited by some fifty monks.

Though the community of monks was fairly insignificant during the Middle Ages, it apparently supplied one monk to the patriarchal throne in 1047, upon the death of the patriarch Shenuda II. He was Anba Christodulus, whose brother Yakub (Jacob) replaced him as abbot of the monastery and who proved to be a man of great holiness and miraculous powers. Al-Baramus also supplied two monks in the seventeenth century to the patriarchal throne. They were Matthew III (1631-1646) as the 100th patriarch and Matthew IV (1660-1675) as the 102nd patriarch, but it also produced a number of outstanding theologians, including Abuna Na'um, and Abuna 'Abd al-Masih ibn Girgis al-Mas'udi, both of the nineteenth century.

Today, the monastery possesses the oldest church that still exists in the region. Furthermore, the monastery still preserves much of its ancient character. The current monastery is dedicated to the Virgin of Baramus, and was probably founded in the late sixth century as a counterpart of the old Baramus facility.

The Enclosure Wall

The enclosure wall of al-Baramus

As a result of these attacks by Berbers and Bedouins, the ninth century patriarch Shenute I built walls around each of the monasteries in the wadi. This specific community was surrounded by a huge, massive enclosure wall which still exists, but for the west side which was built only somewhat later. Their height varies between ten and eleven meters and their width is some two meters. These walls are covered with a thick layer of plaster. Atop the walls a walkway spans their entire length, which enabled the monks to keep a close vigil during the centuries when the Berbers posed a threat from the desert. The monastery entrance is through a small door on the wall's eastern side, though originally the principal doorway was in the north wall. This original entrance had an exterior door opening into a six meter long corridor with a barrel vaulted roof, terminating with an interior door for defensive reasons.

The Church of the Holy Virgin

The Church of the Holy Virgin is situated near the western side of the wall. Of course, it is dedicated to the Holy Virgin. As well as being the oldest church in the Wadi al-Natrun, originating from the last decade of the sixth or the beginning of the seventh century, it is the principal church of this monastery. The Church of the Holy Virgin takes the form of a basilica that includes a khurrus (chorus) with a barrel vaulted roof, preceding the sanctuary, which was believed to have been added in the eighth or ninth century. Against the north wall of the khurus there is a new (1957), small, wooden feretory (a reliquary where the relics of a saint are stored) inlayed with ivory and with glass windows containing the relics of the saints, Moses the Black and Isidore.

This church has a naos (central part of the church) containing a nave, roofed with a barrel vault and receives light through windows placed on the south and north sides, and two side isles. The two side aisles are also roofed with barrel vaults and separated from the nave by strong, oblong pillars that date to the middle ages, but replaced earlier columns. There is the usual marble laggan that is embedded in the floor at the west end of the nave, and there is a finely carved pulpit that stands against the northeast corner of the north aisle, from which the priest explained the Scriptures to catechumens before baptism. In the south aisle at the west end, there is a rare, beautiful, large Corinthian capital ornamented in stucco that is called "St. Arsenius" column", because traditions holds that the saint was accustomed to stop by it to pray.

This church has three sanctuaries, that show elements of widely different periods. A finely carved wooden door dating from the Fatimid period opens onto the main sanctuary (Haykal). This central sanctuary was rebuilt in the thirteenth century and during the pontificate of Patriarch Gabriel III (1269-1271) who carried out significant reconstruction in this monastery, a dome on squinches was added. Under the altar are preserved the relics of Saints Maximus and Domitius.

This church is notable for its huge, partially preserved episodes of a Christological cycle. They represent an exceptional case of monastic wall paintings in Egypt from the medieval period. Between 1986 and 1989, three superimposed paintings were discovered in the church. The oldest of these, attributed to an artist known as "first-Master" who's technique has been described as original and individualistic, dates to about 1200 AD. He decorated the central nave of the church with scenes of the Great Feast. On the southern wall, from east to west, are the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Nativity, the Baptism of Christ, two jars on a table (probably the wedding at Cana), and the Entry into Jerusalem. He also adorned the northern wall with the feat of Pentecost, though other scenes devoted to the cycle of Christ have disappeared.

Vistation, aqarelle copy by Pierre-Henry Laferriere;

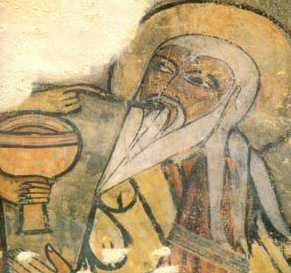

Abraham and Melchizedek

Vistation, aqarelle copy by Pierre-Henry Laferriere

This same artist also produced work on the upper part of the eastern wall of the central sanctuary, where he produced a huge scene of the sacrifice of Issaac, of which only some fragments remain, on the left, and on the right a scene depicting the Meeting of Ibrahim and Melchizedek, which remains fairly complete. In the latter representation, Melchizedek stands before an altar of masonry giving a spoon from the chalice to Abraham. While the depiction of Abraham receiving Holy Communion is not unknown in Coptic art, the appearance of the spoon in this context is utterly unique. These painting flank the central apse (niche) which appears to be the work of a second artist. It is adorned in a traditional manner with twin compositions. Above, Christ is enthroned and below, the Holy Virgin and Child are surrounded by two angels. In the wall of the iconostasis are embedded five stone crosses that probably date back to the early centuries of the Christian era.

On the southern sanctuary's eastern wall are depicted six saints who, from left to right, are St. Pal the Hermit, St. Antony, St. Marcarius led by a cherub, A St. John, St. Maximus and St. Domitius. More saints are represented on the southern wall, including, from left to right, three that are not identifiable, St. Pachomius, Moses the Black (possibly), St. Barsum the Syrian, St. Paphnutius (possibly), and St. Onnophrius.

Central Sanctuary - Apostle

Southern Sanctuary - St. Barsum the Syrian

As of this writing, the restoration of these wall paintings is yet to be completed and more scenes may be uncovered. However, the drawings of "first-Master are of such quality that some must be considered masterpieces of medieval Coptic art.

Chapels and Baptistery

There are two chapels attached to the Church of the Holy Virgin. Attached to the north aisle and probably dating from the fourteenth century is the Chapel of Theodore Stratelates (al-Amir Tadrus) Stratelates is the Greek term for "general", hence, Saint "Theodore the General". The Chapel of St. George (Mari Girgis)_ is located at the west end of the same aisle and dates from either the twelfth or thirteenth century. Near this second chapel is a square room that served as a baptistery and still has its stone font.

The Church of St. John the Baptist

Another church within the complex is relatively new, dating from the end of the nineteenth century. It was commissioned by patriarch Cyril V in a modern Byzantine style. It is situated in the place where an old church dedicated to Saints Apollo and Abib (Phib) once stood. Dedicated to St. John the Baptist, it contains little of interest, except for its epiphany tank, which is the only one in Wadi al-Natrun.

The south sanctuary of this church has been converted into a library containing many manuscripts and old books written in Coptic, Greek, Arabic and Hebrew related to theological, liturgical, historical and artistic matters. The main library, which was once housed in the keep, contains about three thousand volumes, which are kept in several cabinets. The classification was the work of the famous Abuna 'abd al-Masih ibn Salib al-Baramusi, who was known for his great learning.

The Keep

North of the Church of the Holy Virgin is the keep, or tower that the monks call al-Qasr. For centuries it has been the abode of solitaries, the most famous of whom was Abuna Sarabamun (1920). Dating from the ninth century, it is the oldest tower in any of the monasteries at Wadi al-Natrun and its architecture is typical of Egypt's Coptic monasteries. Its entrance, by way of a drawbridge, is on the second floor. It was built over a well and storehouse in order to provide the monks with water in the event of a long siege. The third story is a church dedicated to St. Michael, which the monks continue to use today. It has an altar covered by a dome.

Refectories

There are two refectories on the monastery grounds, but only one is accessible to visitors. It is located next to the Church of the Virgin Mary to the south, parallel to the church's nave. It is a rectangular hall, divided into three domed bays by two pointed arches, measuring about eleven meters long by four meters wide. The domes, or cupolas, have circular openings at the top that provide a very pleasant and atmospheric illumination. Within, a table made of stone takes up the whole length of the building. In the northeast corner there is a stone pulpit from which the reading of the holy Scriptures was proclaimed during the agape after liturgy. This lectern is adorned with a roughly incised cross. Today, the monks use this refectory only for the feasts peculiar to the Coptic liturgical year.

The other refectory, which is older and abuts the west wall of the monastery, is now used as a storeroom. It takes the form of a square room with a central oblong pillar and four domed bays. Here, the monks sat on benches that formed circles, an arrangement that continued until the end of the Fatimid Period when a single, long table replaced them.

Guest House

There is a guest house of nineteenth century Levantine style, comfortably furnished to accommodate visitors. Within the reception hall are pictures of Anba Athanasius, the late metropolitan of Beni Suef; Anba Muqus, metropolitan of Abu Tig; Anba Sawirus, metropolitan of Minya; Anba Banyamin, the late metropolitan of Minufiya; Anba Tuma, the late metropolitan of Tanta; Anba Marcarius, the late bishop of Deir al-Baramus; and Abuna Barnaba, who at one time was the hegumen of Deir al-Baramus.

Recent Renovations

Under Pope Shenuda III, a number of recent renovations were performed at the monastery. An asphalt road to the monastery was built, and there have been several major cultivation projects. In addition, six water pumps, a sheepfold, a henhouse and two generators were added, together with the construction of new residential cells both inside and outside the monastery proper. There is now a clinic and a pharmacy to serve the monks, as well as a spacious retreat center for conferences and a large, two story guesthouse that was opened in January of 1981.

The Ruins of the Old Monastery

Since 1996, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and the Faculty of Archaeology of the University of Leiden have financed the archaeological research on the remains of the site commonly known as Deir Anba Mussaal-Aswad (Monastery of Moses the Black). However, they believe that this is more properly the old Deir al-Baramus.

The old monastery was surrounded by an enclosure wall that was perhaps a somewhat late addition during the 9th century after the community had suffered a very severe attack. It measures about 80 by 65 meters.

Within the old monastery, archaeologists discovered the remains of a square structure measuring some sixteen meters square, in the southeastern corner of the site. It consisted of a structure of one meter thick walls dividing the internal area into nine equal squares. The outer walls were two meters thick. Though its original purpose was at first unclear, it has now been determined to have most likely been a defensive tower, or keep that may have stood some twenty-five meters in height. However, pottery from the 4th or early 5th century found on the site suggest that this tower was built very early for monastic purposes, particularly with regards to what was probably a fairly small community of monks. It has been suggested that this may have originally been built as a Roman military structure in order to defend the Wadi al-Natrun and its salt production. Then, after having been abandoned during the 4th century, it may have been put to use by newly arrived anchorites (religious hermits).

Excavations uncovered a structure in 1998 that, by 1999 proved to be that of a church immediately north of the tower. The walls of the nave are made from poor quality and improvised masonry that suggest that the church was perhaps rebuilt hastily after having been destroyed. This may have been the destruction by Bedouins at the beginning of the 9th century. The actual sanctuary of this church if of better quality, and was apparently reconstructed somewhat later, perhaps at the end of the 9th or the beginning of the tenth century. The altar, which is fairly well preserved, sits atop a one step high podium.

Remains, probably of an earlier structure and consisting of more solid masonry of finely cut limestone blocks, were found in the western part of the church's nave. Since one of these blocks was inscribed with a number of hieroglyphics in high relief, it is very plausible that a pharaonic monument existed in close proximity to this site. This might be consistent with the presence of a Roman defensive tower.

Nearby

About two and a half kilometers northwest of this monastery, there is also the limestone cave of the late pope Cyril VI. Marked by twelve wooden crosses, it is known as the Rock of Sarabamun and has become a popular place of pilgrimage. An iron lattice-work protects the entrance to the site. Within, the one room cave is spacious. It is adorned with numerous pictures and icons of Cyril VI. There are also, in the desert about the monastery, a several caves that apparently continue to be inhabited by hermits.

Return to Christian Monasteries of Egypt

References:

|

Title |

Author |

Date |

Publisher |

Reference Number |

|

2000 Years of Coptic Christianity |

Meinardus, Otto F. A. |

1999 |

American University in Cairo Press, The |

ISBN 977 424 5113 |

|

Coptic Monasteries: Egypt's Monastic Art and Architecture |

Gabra, Gawdat |

2002 |

American University in Cairo Press, The |

ISBN 977 424 691 8 |

|

Churches and Monasteries of Egypt and Some Neighboring Countries, The |

Abu Salih, The Armenian, Edited and Translated by Evetts, B.T.A. |

2001 |

Gorgias Press |

ISBN 0-9715986-7-3 |