Coptic Christian Paintings (Including Icons)

by Jimmy Dunn

With the creation of Alexandria in 332 BC, Hellenization came to Egypt, together with first the art of the Greeks, and then that of the Romans, which began to overlay that of the more ancient Egyptian styles. It was in this setting that Christianity arrived in Egypt and it was here that the rich flavor of Coptic (Egyptian Christian) art evolved.

In Coptic, as well as other Christian art or for that matter, the scenes depicting battles and other notable events on pagan temple walls, were not in themselves art for arts sake. In these early periods, most people were illiterate, and thus many scenes from ancient Egyptian Christian churches might be better understood almost as graphic bibles, depicting famous topics in a manner suited to the common faithful of early Christianity.

In general, it might be said that Coptic Christian art evolved from unsophisticated, crude styles to a refined, highly developed one over time, and spreading from Alexandria southward. The art also varies by region due to the lack of more authoritarian influences in southern Egypt, where early styles were often highly variable.

Stylistically, Coptic painting differs from that of pagan Egypt in its emphasis on animal and plant ornamentation; less naturalistic rendering of the human form; simplified outline, color, and detail; and increasingly monotonous repetition of a limited number of motifs.

The integration of contrasting configurations, including classical, Egyptian, Greek-Egyptian and Persian pagan motifs, as well as Byzantine and Syrian Christian influence, led to a trend in Coptic art that is difficult to define, because a unity of style is not possible to trace. Unfortunately, early collections of Christian art were made without recording details of the sites from which they came, making it virtually impossible to trace artistic development through time. There is no way to tell, for example, how long classical and Greek-Egyptian motifs continued after the adoption of Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire. All that can be said is that Coptic art is a distinctive art, and that it differed from that of Antioch, Constantinople and Rome.

Some of the earliest Christian paintings in Egypt we have records of were probably those in the catacombs of Karmuz in Alexandria. Created towards the end of the third century, they no longer exist, but we know something about their theme. At Karmuz, there was a semi-circular apse within the antechamber that probably served as the Christian sanctuary, or chapel. It was adorned with a frieze that depicted the miracles of Christ which prefigured the Last Supper and the Eucharist. Here, Christ was portrayed enthroned and flanked by Saints Peter and Andrew, who present loaves of bread and fish to him. Left of this, inscriptions identified Christ and the Holy Virgin as being among the guests who witnessed the changing of water into wine at the wedding in Cana. Many of the scenes depict people in nature poses with fluid clothing before woodland backgrounds, a style suggestive of Roman art, particularly with regards to catacombs both in Egypt and in the rest of the Roman world.

Some of the oldest extant Christian art in Egypt can be found in the area of Bagawat in the al-Kharga Oasis in the Western Desert. The paintings in the various chapels and tombs of this region display a notable change from the earlier work in Alexandria, as well as an expansion of the iconographic repertory. Here, the famous Chapel of the Exodus, dating to the fourth century AD, is so called because of its graphic representations of the Hebrew Exodus to the Promised Land under Moses. Within the center of the copula ceiling of the chapel birds weave amongst networks of vine branches, a motif originating in the east but adopted by the Roman world and used extensively in Christian monuments, such as the mausoleum of St. Constantia in Rome (also dating to the fourth century). Other scenes in the chapel, most often rapidly sketched, include Old Testament themes such as the sacrifice of Abraham, Daniel in the lions' den and Noah's ark, among others.

Another building in the region (Bagawat), known as the Chapel of Peace and dating to the fifth century, depicts large, hieratic figures arranged in perfect order. Though a Christian monument, Old Testament scenes are predominate. For example, among these works are portrayals of Adam and Eve after their sin, the sacrifice of Abraham, Daniel in the lions' den, Jacob, Noah's ark and the annunciation symbolizing the new covenant between God and his people.

As Christianity spread south along the Nile River, the oldest places of worship were often established in what was once pharaonic temples, though only occasional remains of the paintings on their wall may still be observed. These places of pagan worship that were converted to Christian use included temples at Philae, Abydos, Deir al-Bahri, Dandara, Luxor, Karnak, Madinat Habu as well as Wadi al-Sebua further south in Nubia, among others.

However, some of the oldest surviving Christian art may be found at Antione, where the Lady Theodosia had herself depicted in her funerary chapel with her arms outstretched in the attitude of prayer. She is flanked by St. Colluthus and St. Mary, who were both natives of he Antinoe area. Here again, the style is quite different then earlier examples of Christian art. Theodosia's high social status is portrayed by her ornate garments with woven decorations as well as the general sumptuousness of her monument. Also depicted is Christ, represented between two angles. These images appear before animal and vegetal backdrops. The poses and faces of those depicted within this monument, as well as the folds of clothing treated in a simplified manner, place the images in the Byzantine context of the fifth or sixth centuries.

The rock church of Deir Abu Hinnis near Antinoe, which was hewn within an ancient quarry, has one of the oldest examples of ecclesial (related to a church) painting, which dates from the end of the sixth century. A frieze here which continues uninterrupted between scenes and is characterized by a variety of poses, depicts many episodes of Christ's life, including the massacre of the innocents by Herod, the flight of Elizabeth and John, the dream of Joseph and the Holy Family's flight into Egypt. Some evolution of Christian is recorded upon the walls of this church, for another frieze dating from the eighth century depicts Zechariah's life, with more rigid poses and stiff olds in the clothing. Then, within panels, a separate representation portrays the wedding at Cana and the resurrection of Lazarus.

The use of panels also became a common fashion among monastic complexes, particularly at Bawit and Saqqara, which flourished between the sixth and eighth centuries AD. In the oratories of the cells and in churches, the walls could present up to three tiers of adornment. The lowest tier of large panels would include a geometrical or floral motif, while the upper tiers show tall figures of standing monks and saints, or perhaps scenes narrating a story. This method seems to have looked back upon older methods, for in the pagan necropolises of Tuna al-Gebel and Alexandria, this same artistic device was in use during the third and second centuries BC. However, the scenes in at Bawit and Saqqara show cycles that are unique because of their early date, the variety of images and the superior workmanship of their artists. Here, scenes from the Old and New Testaments, such as the story of David, the cycle of the nativity and annunciation, the baptism of Christ and others mingle with depictions of equestrian saints and rows of saints and monks. Some niches are adorned with depictions of the Holy Virgin seated on a throne holding the baby Jesus in front of her or nursing him, which are references to the divine motherhood of the Holy Virgin defined by the council of Ephesus in 431 AD.

Christ enthroned and rows of saints surrounding the

Holy Virgin and Child at the Monastery of Apollo at Bawit

However, the most amazing images are those of the apocalyptic visions drawn from the biblical texts of Ezekiel, Isaiah, Daniel and John. Here, Christ is seated on a fiery chariot and surrounded by the figures of the four living creatures flying on seraphim wings strewn with eyes, while two angles bow as a sign of veneration. In the background is a starry sky, with the sun and moon personified by busts as was the convention in antiquity. They symbolize eternity. On a lower tier, the Virgin Mary stands among the apostles as an orant (a praying or kneeling figure), or seated on a throne with the baby Jesus, who she nurses. These represent a common composition that suggests the links between the apocalyptic vision with the twofold event of the death and resurrection of Christ and then his second coming at the Last Judgment.

Kellia (the Cells), just outside of the Western Delta, was an early center of isolated hermitages during the fourth century AD that grew, by the end of the seventh century AD, into a region of small anchoritic (hermit or near hermit) colonies. Here, there were no great compositions of narratives scenes such as those at Saqqara and Bawit. The scenes here were probably influenced by the the lifestyle of these lonely hermits. Adorning their walls were the likewise isolated examples of a bust of Christ, warrior saints and depictions of St. Menas. Other scenes are almost secular, depicting lambs and other animals such as tucks, lions, and quail (including unicorns), together with lush vegetation and scenes of the Nile river. Crosses, though not depicting the crucifixion are also common, sometimes adorned with jewels or weighed down with foliage, pomegranates, censers or small bells. Rather than the death of Christ, these crosses evoke his triumph over death and his glory.

In Coptic art, Christ was almost always depicted as triumphant, reborn, benevolent and righteous and this is one of the most significant and continuous characteristics of Coptic art. In fact, the early Egyptian Christians did not delight in painting scenes of torture, death or sinners in hell.

One cross (sixth or seventh century AD) portrays, in its center, the bust of Christ giving a blessing. This scene was also found in a mosaic in St. Apollinaris in Classe at Ravanna, Italy, on flasks from the Holy Land in Monza and Babbio, Italy dating from about the same period. It was repeated in a Coptic manuscript dated from 906 AD, in Nubian paintings at Faras and Abdallah Nirqi dating to the ninth through eleventh centuries, and in Armenian manuscripts from the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries AD.

The mid-seventh century brought the Arab conquest and Islam to Egypt, but this did little to stop the flow of Christian art in Egypt. Instead, the archaic Muslim incursion into Egypt saw a blossoming of great Christian iconographic programs, often covering more ancient works. This was no more true then in the monasteries of the Wadi Natrun. For example, an annunciation was discovered in the Church of the Holy Virgin which had been covered over by a scene depicting ascension in about 1225. The annunciation could have been created as early as about 710 AD, when Syrians purchased the monastery. This remarkable work is not only inspiring because of its grand style, but also its rich iconography. It depicts the Holy Virgin, seated on a throne, listening to the archangel's message. She is surrounded by four prophets, consisting of Moses, Isaiah, Ezekiel and Daniel, holding scrolls with Coptic inscriptions. In the background is the town of Nazareth. This theme is unique to Egypt.

A large part of this church's wall had been covered by up to three coats of paint. Therefore two paintings of the Virgin and Child, dating from the second half of the seventh century were discovered, together with another depicting Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, who is holding the souls of the blessed in Haven. Later paintings adorn the walls of niches, including the ascension (rising of the body of Jesus into heaven), annunciation (when the Holy Virgin was told she would bare Christ), nativity (the birth of Christ) and dormition (The Holy Virgin's death, or "falling asleep").

Top: A scene from the Church of the Holy Virgin in the Monastery

of the Syrians at Wadi Natrun of the Dormition; and bottom: of the nativityOther monasteries at Wadi Naturn, such as al-Baramus and Anba Bishoi (Pshoi) also provide us with vestiges of ancient Christian art. Here, we find the encounter of Abraham with Melchizedek, which is in the simplistic style and colors of the oldest monastic paintings.

Also, in the monastery of St. Marcarius, within the sanctuary of Benjamin in the church of St. Macarius, we find a unique use of wood panels. For example, the twenty-four elders of the book of Revelation are depicted seated upon their thrones and embellished with precious stones, each holding an ornate chalice, but each of their heads was painted on a wooden disk. At the base of the cupola, each triangular wooden panel was painted with an immense figure of a winged seraph, with wings unfolding, to protect the sanctuary. Within the interior curve of the entrance arch was woodwork covered with medallions showing the still recognizable scenes of the embalming and burial of Christ. On the west wall, Christ is flanked by two angles beside equestrian and other saints. These paintings may date from a restoration in about 830 AD under the patriarch Jacob.

Next to this in the sanctuary of St. Mark, the adornments could date from 1010 through 1050 AD, when the evangelist's reliquary was brought to the monastery. This would reconcile with the characteristics of the Islamic Fatimid style, consisting of pointed arches and squinches. Here, the decorative theme, which is divided into two tiers at the level of the pendentives and in their squinches at the base of the cupola, is more complex. The upper tier is adorned with scenes from the Old and New Testaments, the former prefiguring the latter while the lower tier depicts angles, saints, the head of Christ, seraphim and the scene of the three young men in the furnace. These figures appear as the witnesses of the Christian faith and its intercessors, either by their ascetic life or their martyrdom.

For twelfth century Christian art, we make look to the monasteries of Deir al-Shuhada and Deir al-Fakhuri in the desert near Esna (Isna) At Deir al-Shuhada, the image of Christ enthroned is depicted three times and two of these paintings show the apocalyptic vision that we find throughout Egypt. One of these portrays the bust of the Virgin Mary and St. John, which invokes the theme of the Deesis ("intercession" in Greek), which the Byzantine world linked with the Last Judgement. On another, Christ's feet surmount the sea of crystal mentioned in the book of Revelations (4:6) to symbolize the quenching of the saints' thirst and the separation of paradise from the earthly world.

There exits another scene with the theme of the deesis at Deir al-Abiad, better known as the White Monastery, in Sohag. It appears in the south apse beneath the depiction of a large cross around which a piece of cloth is wound. This dates to between the eleventh and twelfth century AD. A variety of crosses may also be found in the nave of the church, which is now open to the sky. Some are identical to the once in the south apse, while others are entwined with designs and are similar to those that can be found in manuscripts dating to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Christian art from the thirteenth through the fifteenth century is particularly well preserved in the Church of St. Anthony in the famous monastery by the same name near the Red Sea coast. The church was built at the beginning of the thirteenth century and has remained almost completely unaltered since then. The original decorations were undertaken by Master Theodore around 1232 -1233, while another painter worked in the monastery sometime before 1436. He was known as the painter of the paschal cycle. Hence, the paintings follow an iconographic theme established from the start, a fact which provides a cohesion rarely found anywhere else.

At the entrance to the church, visitors are today welcomed by large equestrian saints and holy monks. As they move into the sanctuary, other saints and patriarchs adorn the walls. Within the sanctuary, their are several tiers of depictions that lead the eyes of the beholders from scenes from the Old Testament to the twenty-four elders of the Apocalypse, then to the Holy Virgin and Child on the east wall, and to the enthroned Christ above. There is a bust of Christ Pantocrator (ruler of the universe) in the cupola and there, he is surrounded by angels and seraphim (basically, a type of six winged angle). In the adjacent chapel called the Chapel of the Four Living Creatures, we once again find the theme of the apocalyptic vision of the enthroned Christ, flanked by the Holy Virgin and St. John.

Icons

The word "icon" is derived from the Greek "eikon" or from the Coptic word "eikonigow" both of which are similar in their pronunciation. Icons are actually somewhat difficult to define, even though they have a prominent place in the life and worship of the Eastern Orthodox Churches. They are representation or picture of a martyred or sanctified Christian personage so that they usually depict specific saints, group of saints, angels or Christ, as opposed to larger, more complex scenes. Sometimes they are purely portraits of a specific being, with little or no background. However, we also find groupings such as the Virgin Mary and Child and sometimes their might be somewhat elaborate backdrops to the persons depicted. However, other icons can depict biblical events, and other religious topics as well, though these seem to be in a minority among modern icons. Furthermore, the term's wider definition can apply to many paintings of a religious nature, whether movable or fixed.

In the earliest development of icon painting the artists worked directly on the wooden panel but later they began to cover the surface with a soft layer of gypsum onto which lines could be chiseled to control the flow of liquid gold.

Historians date the appearance of the iconographic style to the first three centuries of Christianity. Some archaeologists believe that icons were first popular in people's houses and later began to appear in places of worship, probably at the end of the 3rd century. By the 4th and 5th centuries A.D. their use was widespread. According to the Arab historian Al Makrizi, Pope Cyril I hung icons in all the churches of Alexandria in the year 420 A.D. and then decreed that they should be hung in the other churches of Egypt as well.

When Egypt turned increasingly towards Syria and Palestine after the schism in the fifth century, her saints and martyrs began to take on the stiff, majestic look of Syrian art. There began to be an expression of spirituality rather than naivety on the faces of the subjects, more elegance in the drawing of the figures, more use of gold backgrounds and richly adorned clerical garments.

The idea behind the use of icons in the Early Church is due to the unique experience the Church faced. Most Christians converts came from pagan cultures, many of them were illiterate. They had difficulty understanding Biblical teachings and their spiritual meanings, as well as the historical events that took place in the Bible and in the life of the Church. Therefore, the leaders of the Early Church permitted the use of religious pictures (icons) because the people were not able to assimilate Christianity and its doctrine unaided by visual means. Therefore, these presentations aided the faithful in understanding the new religion.

Whether movable or fixed, these images must have been venerated as icons. The oldest icons in Egypt appear to go back to the fifth or sixth century. Among these, seven come from one tomb in Antinoe, among which are depictions of saints, a veiled woman, an angel and all very similar to Roman-Egyptian funerary portraits that were found in the Fayoum dating from an earlier period. Thus, the techniques of tempera painting on wooden panels survived in the art of the icon. In fact, just as the Fayoum portraits were placed in graves, the early Christian icons of Antinoe may have been placed near the dead to obtain the saint's intercession before God on behalf of the deceased.

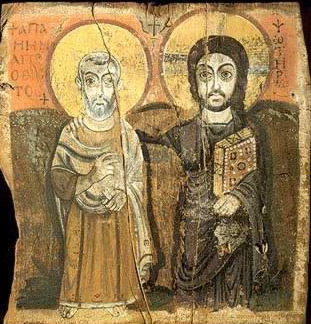

The early Coptic Christian icons that followed such as a painting of Christ and Abbot Menas now in the Louvre Museum, of Bishop Abraham now in Berlin and of Saint Theodore in the Coptic Museum, differ from Byzantine works of the same period and are characterized by a local, monastic style. Facial features are simplified and painted with flat, muted colors, while the folds in clothing are spare and either vertical or curved.

By the seventh century, Coptic icons seem to have fallen from favor and in fact do not reappear until the eighteenth century. The reason for this is uncertain. The Coptic Church maintains that there was a movement to eliminate icons from churches on the grounds that they were being worshipped as graven images, prohibited by Exodus 20:4-5, though this decision may have very well have been influenced by Egypt's Muslim masters as well, for Icons did not disappear from much of the rest of the Eastern Christian world

However, from the eighteenth century on, icons were often dated and even signed. Hence, from the eighteenth century on, we learn that many of the painters were foreign, though in the simplification of forms, the use of flat colors and the bold delineation they are seen as Coptic in character.

The Characteristics of Coptic iconization follow certain symbolism that carries a meaningful message, though many of these attributes may be found in icons outside of the Coptic Church. Some of these characteristics are:

-

Large and wide eyes symbolize the spiritual eye that look beyond the material world. The Bible says "the light of the body is the eye: if therefore thine eye be simple, thy whole body shall be full of light" [Matthew 6:22].

-

Large ears listen to the word of God. The Bible says "if any man have ears to hear, let them hear" [Mark 4:23].

-

Gentle lips to glorify and praise the Lord, for the Bible says "My mouth shall praise thee with joyful lips" [Psalm 63:5].

-

Small mouths, so that they cannot be the source of empty or harmful words.

-

Small noses, because the nose is sometimes seen as sensual.

-

Large heads, which imply that the figure is devoted to contemplation and prayer.

Some icons portray Saints who suffered and were tortured for their faith with peaceful and smiling faces, showing that their inner peace was not disturbed, even by the hardships they endured, and suffered willingly and joyfully for the Lord. When an evil character is portrayed on an icon, it is always in profile because it is not desirable to make eye contact with such a person and thus to dwell or meditate upon it.

Icons have a special significance in the Eastern Christian churches. Generally, Coptic Christians make no distinction between the qualities and characteristics of an icon and those of the person or people represented by the icon. Whatever powers the actual being portrayed had during his or her life, so to has the icons representation. Hence, in a certain respect, miraculous properties are attributed to Coptic Christian icons, as well as others in the Eastern Orthodox churches. In fact, there are many more icons from the Byzantine and Russian churches that are attributed with miraculous powers than in the Coptic Christian realm.

However, it should be noted that the modern Coptic Christian Church discourages the veneration of icons themselves. They make it clear that it is not the icon that must be respected, but rather the person or event it portrays. Yet, a traditional legend in the church would indicate otherwise.

It is said that an icon the Savior made without hands, goes back to the first century when king Abagar of Edessa (located between the two rivers, Euphrates and Tigris, an area in eastern Iraq) sent a message with his envoy Ananius to the Lord Jesus Christ to ask if He could visit the king to heal him. The king suffered from diseases and he wished that Christ would come and live in his kingdom. Ananius the envoy was a talented artist, and tried to paint a picture of the Christ. However the glory and the perfect appearance of the Lord was so great that he was unable to do so. The story says that the envoy went back to the king with a piece of cloth that had an image of Christ's face. The image of the Holy Face of Christ healed the king of his diseases in the absence of Christ himself.

Therefore, any number of icons in Egypt are thought to have miraculous powers and their seems to be no specific need for a Coptic Icon to be ancient, though a few are. Some of the most venerated icons in the Coptic church include those of:

-

Saint Damian and her forty virgins in the Shrine of Saint Damiana, near Bilqas, Mansoura

-

Saint George in the Old Church of Saint George, Mit Damsis, near Mit Ghamr

-

The Holy Virgin of the Tree of Jesse in the Church of the Holy Virgin, Harat Zuwayla, Cairo

-

They Holy Virgin in the al-Mu'allaqa Chruch of the Holy Virgin, Old Cairo

-

Saint Barsum al-'Aryan in the Church of Saint Barsum, Ma'sara, near Helwan (south of Cairo)

-

Saint George in the Church of Saint George, Biba, Beni Suef

-

Saint Theodore in Dair al-Sanquriya, Bani Mazar

-

The Holy Virgin in the Church of the Holy Virgin, Gabal al-Tayr

-

The Holy Virgin in the al-Muharraq Monastery of the Holy Virgin, al-Qusiya

-

Saint Mercurius at the Monastery of Saint Mercurius, Qamula

-

Saint George at the Monastery of Saint George, Dimuqrat, Asfun

Except for the icon of the Holy Virgin in the Harat Zuwayla, dating to the fourteenth century, the others listed above date to the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries.

Most of the icons with miraculous powers fall within five classifications, consisting of the fertility-granting icon, the healing icon, the weeping icon, the bleeding icon and the light emanating icon.

While western Christian churches have their stained glass and some statuary, we may sum up by saying that visually, the Eastern Orthodox Churches and the Coptic Christian Churches in particularly seem to be much more rich in visual art then their western counterparts (with a few exceptions).

See also:

Ancient Coptic Christian Fabrics

Return to Christian Monasteries of Egypt

References:

|

Title |

Author |

Date |

Publisher |

Reference Number |

|

2000 Years of Coptic Christianity |

Meinardus, Otto F. A. |

1999 |

American University in Cairo Press, The |

ISBN 977 424 5113 |

|

Christian Egypt: Coptic Art and Monuments Through Two Millennia |

Capuani, Massimo |

1999 |

Liturgical Press, The |

ISBN 0-8146-2406-5 |

|

Churches and Monasteries of Egypt and Some Neigbouring Countires, The |

Abu Salih, The Armenian, Edited and Translated by Evetts, B.T.A. |

2001 |

Gorgias Press |

ISBN 0-9715986-7-3 |

Last Updated: June 14th, 2011