The Gilf Kebir, Part II

by Allen Watson

At Gilf Kebir, a number of wadis intersect and scar the plateau, and many of these are very beautiful, but they also contain considerable rock art.

We will begin by examining the Northern Gilf, where, in contrast to the prolific number of painted shelters around Wadi Sura to the south, there are few rock art sites. This is surprising given that three of the main wadis in this area have considerable vegetation. One of the early explorers, Almasy, thought that this was because they were still raging mountain streams during prehistory. He was mistaken, but still there is no explanation for the lack of rock art sites.

Waid Hamra is red, and the red sand dunes here, cascading down the side of a black mountain are indeed beautiful. It is said that Almasy wanted Rommel to land troops on top of the Gilf and bring them down into Wadi Hamra. Clayton found plenty of trees and many Barbary sheep. When Mason and company entered the wadi they followed it as far as it would allow and almost ended up on the other side. Mason observed that the wadi "lies so far inside the Gilf Kebir that it is nearer to the western cliff than to the eastern" and that "the head of the Wadi Hamra splits up into three separate heads, the longest one reaching southward until it almost meets the head of another larger wadi which leads down to the western plain."

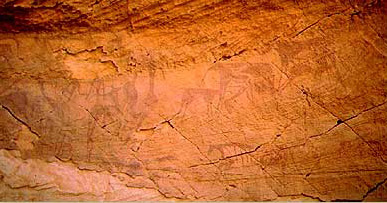

Within the Wadi Hamra are three groups of rock art sites. All are engravings, in a fairly crude style, depicting wild fauna. Based on the style and state of weathering they seem to belong to the earliest phase of rock art in the region. The first group, discovered by Rhotert, lies near the head of the valley, but apparently is very difficult to find. The second group is also difficult to find, but lies on a low rock face on the east side of the valley in the middle section. They record animals, many of which are unidentifiable, including three figures that are almost certainly rhinoceros. This is unique to the eastern Sahara, and may also point to the extreme age of these engravings. The third group is at the end of a small side wadi not far from the previous group. They show engravings of animals, including mainly giraffes.

There is also one site known from the northeastern edge of the Gilf, inside a small wadi about 40 kilometers to the north of the mouth of Wadi Hamra.

The Wadi Abd al-Malik is much larger than the Wadi Hamra. It enters the Gilf Kebir from the north and runs south for almost the entire length of the northern half of the Gilf.

This is the first valley the Clayton-East-Clayton/Almasy Expedition of 1932 saw from the air but were unable to find on foot. They were sure that it was Zerzura. In 1938, Bagnold and Peel came to the Wadi Abd al-Malik to look for a well that natives said existed but Almasy was unable to find. They looked for three days and then Peel entered a small grotto and found some more rock art. It is on the eastern side of the eastern branch of the wadi about 16 kilometers above the main fork. The paintings were on both walls, dust covered. They depicted some cattle and another animal, probably a dog. The paintings were dark red, red and white and white only. Bagnold tells us that when he was looking for this well, "there being as usual in the Gilf no possible way down for a car from the plateau to the valley within it, we had to climb down and walk. We walked a total of more than 30 miles along the soft sandy floor of that wadi, during two stifling days when a khamsin wind was blowing form the south."

Later expeditions have been able to "climb down" at a point called lama Monod Pass, using modern 4x4s. As one travels north out of the Wadi Abd al-Malik, one is only about 10 to 12 kilometers east of the Libyan border. At the northern entrance to the wadi stand three dunes, barriers but easily managed.

Today we believe that all of the rock art in this wadi are in the middle section of the main eastern branch. Despite a number of thorough surveys in the past several years, no sites have been found in the lower course and the western branch. In addition to the one found by Bagnold and Peel, another was found in 1999 not far away on the opposite bank. Most of these engravings were rather crude. Then, in 2002, the Fliegel Jezerniczky Expeditions found another one farther north, along the east side, in a small shelter near a dry waterfall. This site contained engravings of giraffes, cattle and other unrecognizable animals.

The third valley, Wadi Talh, is nearby, but although it was explored in the early part of the twentieth century, no work has been done in recent years and little is known about its environment.

There are more valleys on the southeastern side of the Gilf. One must remember that the Gilf Kebir has two halves, a northern and a southern one, which are separated by a narrow ridge of land.

Wadi Mashi, the Walking Valley, was so named because the mountain seems to walk, for they disappear and reappear as one journeys near. It cuts about 15 kilometers southwesterly into the southern Gilf in its upper northeastern corner. There have been no discoveries in this wadi.

Wadi Dayyiq, the Narrow Valley, has a major reduction station where ancient people manufactured their tools by breaking them from hard rocks and chiseling and pounding them into various shapes like knives, blades and arrows. The site measures 12 by 20 meters and probably served several communities in the southeastern wadis of the Gilf.

To the east of Wadi Dayyiq, a fully loaded ammunition truck from the Long Range Desert Group was found in 1992, almost 50 years after the end of World War II. The Bedford truck held seven to eight tons of now volatile explosives. When Military Intelligence was notified and found the truck, they filled it with petrol and it started. It is now at the al-Alamein Museum. There are other war artifacts around the Gilf. A Ford lorry, probably used by the long Range Desert Group, is located to the south. Another Ford lorry and a General Motors stake-bed lorry are ten kilometers southeast of the southern tip of the Gilf.

Wadi Dayyiq sits below Wadi Mashi and cuts into the Gilf to the northwest. Then it turns southwest. There are three major side valleys and a few bays. It is followed by al-Aqaba al-Qadima, the Old Obstacle, another wadi cut into the Gilf.

Wadi Maftuh, the Open Valley, cuts deeper into the Gilf than the two previous valleys. Its entrance is rather large with an island in the center. There are a number of deep side valleys, but the main valley, after the island, moves northwest and then southwest. It to has a few smaller side valleys.

Wadi al-Bakht, Valley of Luck or Chance, extends 30 kilometers into the heart of the Gilf Kebir. The area was first explored by O. H. Myers in 1938. Because of the war, Myers' work was not published. In 1971, W. P. McHugh worked on Myers' papers for his Ph.D. In 1978, the Apollo-Soyuz team visited the site.

When the Bagnold-Mond Expedition visited the Wadi al-Bakht in 1938, about ten kilometers into its canyon-like valley, the way was blocked by an enormous 30 meter high dune situated atop a former lake bed. By the 1970s, when the Combined Prehistoric Expedition came to the Wadi, the dune had been breached.

In 1938, four distinct concentrations of artifacts were identified. Site Fifteen is 40 to 50 meters below and to the east of the dune. Site Sixteen, called upper dune and lower dune, are on the dune., and Site Seventeen is on the edge of the lake mud, 50 meters above the dune.

People lived in this valley for many centuries. The entire area, including the dune face, is littered with ancient artifacts. There are grinding stones, pottery, ostrich eggshells and bones. Two kilometers beyond is a Neothlithic site. In all probability the people lived on the dune first, then ventured closer to the lake for settlements.

There is an abundance of pottery, mostly dated to 6930 BC. This is of the same age as the pottery at Nabta, near the Darb al-Arbain, but the style and construction are entirely different. One shape is straight-sided, another is molded. The pottery is black, reddish-yellow or brown, while the Nabta pottery is predominately brown to gray.

There were also cattle. All the rock drawings in the area of the Gilf Kebir and Uwaynat show an abundance of cattle. The archaeological remains have been sparse, however, though the site is deep and the work has not progressed very far. Evidence of cattle in the Western Desert, especially here, at Bir Kiseiba dn at Nabta, can be dated to as early as 9000 to 9800 BC.

Only one ridge separates the entrance of the Wadi al-Bakht from its northern neighbor, the Wadi Maftuh. The valley runs fairly straight due west with a number of small bays.

Wadi Wasa is the Wide Valley, and like all of its sister wadis, was created by water erosion in the distant past. It drained east. Wadi Wasa is the most amazing valley in the Gilf. It begins on the eastern side, makes its way through the Gilf in a predominately southwesterly direction and emerges on the western side. There are a few islands and dozens of major side valleys, one of them named Wadi al-Ard al-Khadra. It would be easy to get lost here and very complicated to find one's way through the valley.

There is only one known rock art site in this region of the Gilf, above Wadi Wasa, called Shaw's Cave, after its discoverer who unearthed it in 1936. Also known as Mogharet el kantara, an overhang forms a low shelter, and the paintings depicting mainly cattle and a homestead scene, are located about 40-50 centimeters above ground, in an almost continuous line along the rear of the shelter. These cave drawings were not completely published until 1997. It contains three groupings of rock art.

The Wadi al-Ard al-Khadra, or the Valley of the Green Earth, along the southern part of the Gilf, runs north, then curves southwest. Approximately 35 kilometers long, the Wadi is a huge steep-walled valley that emerged from within the Wadi Wasa, It has two major branches and a number of bays and smaller routes.

Similar to Wadi al-Bakht, concentrations show that this valley was also blocked by a dune to form a small amphitheater basin. The dune is located about five kilometers from the head of the valley. It has probably been in place since prehistory and once helped create a lake.

There is evidence of stream erosion in post-Oligocene times. When the wet phase ended, dunes marched into the valley. Dozens of sites show human habituation. The Apollo-Soyuz team worked here in 1979.

The lake probably disappeared around 5200 BC, and this valley has therefore been abandoned for many thousands of years.

Eight Bells is the result of a huge, 3,400 square kilometer drainage system of ancient times which discharged to the south hundreds of kilometers beyond the present plateau scarp. It is the only wadi on the east to drain south into a much larger water system. McCauley and his group tell us that Lake Chad, which this drainage system fed, in 5000 BC filled the Bodele Depression to a level of at least 320 meters, extending to within about 600 kilometers of the south margin of the Gilf Kebir. He believed that the Eight Bells drainage network may have discharged from the Gilf uplands into this great inland basin.

On the western side of the Gilf Kebir are more Wadis. Though the entire Gilf Kebir lies in Egytpt, one is very, very close to Libya, and many of the wadis on this side have not much been explored or even given names.

The Wadi Sura (Sora), known as Picture Valley, contains the now famous Cave of the Swimmers. It is not really a wadi, but rather a sheltered inlet among a promontory and a couple of detached outliers of the main plateau. After Almasy found the rock pictures in the Giraffe Caves at Ain Doua, a Wadi in Gebel Uwaynat, he came back in October of the same year (1933) with the Frobenius Expedition. They came especially to look for rock art. All along the valleys of Uwaynat they found it. Then Almasy began to explore the western slopes of the Gilf, the same area that P. A. Clayton had previously explored. Here he found a number of paintings and drawings including the swimmers. Their importance does not lie solely in their beauty. They attest to the presence of a lake, which does not exist at the present time. It was Almasy who named the place Wadi Sura.

Actually, there are three or four caves situated at the head of a short amphitheater-like wadi some three miles south of the entrance to the main wadi. Peel provided us with detailed descriptions of the two caves that contain paintings. Actually, these are more hollows at the base of the cliff, and lie at the right entrance of an inlet, no more than 50 meters from the outer cliff face, at the base of a spur of the main plateau. There is a small watercourse in front of the main caves, which can be followed for some distance into the cliffs,

The first cave is on the right (south) as one enters the wadi. Here one group of paintings remains intact, showing two dozen figures of men and cattle all in dark red and white, along with female figures and a group of archers. In a style called "balanced exaggeration" by Winkler, the men have broad shoulders, narrow waists, triangular torsos, exaggerated rounded hips and long, tapering legs and arms. Their feet and hands are rarely shown, while their heads are round blobs. Almost all of the figures carry bows, some of which are being used. They are all naked. The cattle in the scene have tapered limbs and long thin tails. The paintings are similar to many at Gebel Uwaynat and are undoubtedly the work of the same people, Autochthonous Mountain Dwellers.

The second, larger cave is some twenty yards to the north, left of the first one, and has a larger number of illustrations, including cattle, ostrich, dogs and giraffe. The bulk of paintings here, however, are of men, with well over a hundred figures represented. Many more paintings are damaged and the original number may well have been twice or three times that figure. Here the figures are crudely painted. The heads are round blobs, the torsos thick, the limbs clumsy, the hips narrow and the feet only indicated. Hands appear only on the larger drawings. The colors are mostly dark red, with bands of white around ankles, wrists, upper arms and below the knees.

Then, of course, there are the swimmers. These are small and painted in red. They are only ten centimeters long with small rounded heads on thin necks. The bodies are rounded and the arms and legs are thin. All appear to be swimming. Some appear to be diving.

There are also figures in yellow. One figure in dark red stands between two in yellow with an arm outstretched to each. The yellow figure on the right is small and may be a child. The grouping may of course be accidental, but if not, the group may be intended to represent a union between two different groups, or even a marriage, though there is no indication of sex in any of the figures.

About 800 meters north from the main caves, there is a solitary rock on the valley floor, with a small underhang. In this shelter there are a few very faded paintings and engravings of humans and giraffes.

Wadi Sura lies near the tip of a broken rocky promontory, that is an offshoot of the main bulk of the Gilf Kebir. To the north, the country is very picturesque, with many isolated blocks and valleys in between. It was here that Patrick Clayton discovered, in 1931, a couple of faint engraved giraffes on an isolated block near the entrance of a broad valley. On the other side of the same rock Almsy and party found further faint engravings in the spring of 1933.

In the same general vicinity, Almsy and Rhotert located a number of lesser sites during the autumn 1933 expedition (at the same time when the main caves were discovered). One is an engraving of a 'Nubian' type skirted woman, and three painted shelters whose exact location remains a mystery. After repeated detailed surveys of the area by many in recent years, we know of no one who has found them.

Very close to the rock with the engraving of the skirted woman, Giancarlo Negro and party found a low shelter with some paintings in the mid-eighties (which remain unpublished), and the team found three more sites with very faint and damaged paintings close by in March 2001.

In 1991 Giancarlo Negro and Yves Gauthier made a detailed survey of the area encompassing a broader area. During this survey, they have found a large and well preserved shelter with many white painted cattle, and a curious dark feline like figure near a negative hand print. Another shelter was found at some distance with some damaged figures in the same style as the 'cave of swimmers'.

In February 2001 Werner Lenz and party found a beautiful shelter some distance from Wadi Sura proper, which contains a series of very well preserved overlapping scenes of several periods (including faint engravings that were painted over, and some small erased figures of the 'cave of swimmers' style). On the ceiling there is a unique scene of two negative hands, the colors as vivid as if it were made yesterday.

During the March 2003 Fliegel Jezerniczky expedition, they also have found a small shelter near the white painted cattle reported by Gauthier and Negro. It contains a scene of calves tethered to a tree, in a style identical to that at Jebel Uweinat. This scene, found at several other locations at Uweinat, is unique in it's very high degree of standardization across a large geographic area, reminiscent of the rigidly standardized iconography of ancient Egypt.

Roughly halfway between Wadi Sora and the Aqaba Pass, Giancarlo Negro and Yves Gauthier also found, but did not publish in the mid eighties, a low shelter with scenes of "roundhead" type figures.

Finally, there is Al-Aqaba, the Difficult. It is a pass leading from the desert floor up to the top of the Gilf. As its name implies, it is not an easy ascent, but it was used by the explorers in 1930 to get their cars onto the plateau. Almasy believed that his friends from the Long Range Desert Group mined this pass during the war and he therefore went south in his dash across the desert in the summer of 1942. Shaw, on the other hand, maintains that al-Aqaba was never mined. Today, rumor has it that the Egyptian Army, in order to thwart the Libyan smugglers whose tracks are evident all over the southwestern desert, mind al-Aqaba. At any rate, we do not wish a tourist to be the first to find out.

Recently, near the Gilf, scientists have discovered a meteor crater field. Some 160 impact structures are known on Earth, among which most are single craters and very few impact fields. Impact crater fields result from meteor showers that can produce tens of kilometer size impact structures in a single event. Only a few such field are known on earth, and the one near the Gilf is the newest, and largest of these. This particular one features at least 50 small circular craters covering an area of 4,500 square kilometers.

See Also: