Funerary and Other Masks of Ancient Egypt

by Jimmy Dunn writing as Jefferson Monet

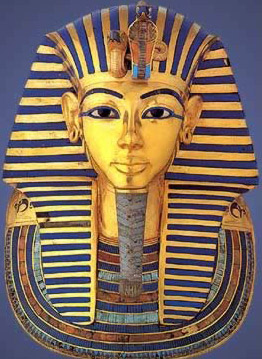

Many people interested in Egypt are familiar with funerary masks, used to cover the face of a mummy. An example, of course, is the famous funerary mask of Tutankhamun now in the Egyptian Antiquities Museum in Cairo, though certainly most funerary masks were not made of solid gold. However, living persons in ancient Egypt might have employed transformational spells to assume nonhuman forms. Specifically, masked priests, priestesses or magicians, disguising themselves as divine beings such as Anubis or Beset, almost assuredly assumed such identities to exert the powers associated with those deities. Funerary masks and other facial coverings for mummies emphasized the ancient Egyptian belief in the fragile state of transition that the dead would have to successfully transcend in their physical and spiritual journey from this world to their divine transformation in the next. Hence, whether worn by the living or the dead, masks played a similar role of magically transforming an individual from a mortal to a divine state.

On various artifacts, we find numerous examples in art, beginning with the Predynastic palettes (such as the Two-Dog palette), representations of anthropomorphic beings with the heads of animals, birds or other fantastic creatures. Some of these are understood to have probably been humans dressed as deities, though the ancient Egyptians probably saw them as images or manifestations of the gods themselves. This was probably most evident in three dimensional representations such as the Middle Kingdom female figure from Western Thebes (modern Luxor), now in the collection of the Manchester Museum and sometimes referred to in earlier texts as a leonine-masked human. Though most certainly a human dressed as an animal, this figure was surely considered an image of Beset.

Two dimensional depictions are more difficult to interpret. The question of the extent to which these depicted masks were used in Egyptian religious rituals has not yet been satisfactorily resolved for all periods of ancient Egyptian history. This may be due to intentional ambiguity. An example is one very common depiction rendered in many mortuary scenes that records the mummification of a body by a jackal-headed being. Such representations may document the actual mummification rites performed by a jackal-disguised priest, though it may also be interpreted as commemorating that episode of the embalmment by the jackal god Anubis in the mythic account of the death and resurrection of the god of the dead, Osiris, whom the deceased wished to emulate. Another example is a ritual procession of composite animal and human figures, identified in the accompanying texts, as the souls of Nekhen and Pe, who carry the sacred bark in a procession detailed on the southwestern interior wall of the Hypostyle Hall in the Temple of Amun at Karnak. Scenes such as this may either be literal records of the historic celebration performed by masked or costumed priests, or alternatively they may represent a visual actualization of faith in the royal dogma, which claimed categorically that the mythic ancestors of the god-king legitimized and supported his reign.

Irregardless, it is thought that the ancient Egyptians did in fact perform some ritual ceremonies wearing such masks, though these ritual objects from the archaeological record are rare. Perhaps this is due to the fragile and perishable materials from which such masks may have been constructed (though surely some were made from gold, thought to be the skin of the gods). We do have an example of a fragmentary Middle Kingdom Bes-like or Aha (perhaps an ancient god and forerunner of Bes) face of cartonnage recovered by W.M. Flinders Petrie at the town site of Kahun. However, this relic may not have been a mask even though it does appear to have eye holes. There was also an unusual set of late Middle Kingdom objects found in shaft-tomb 5 under the Ramesseum that included a wooden figurine representing either a lion-headed goddess or a woman wearing a similar kind of mask, which probably connected in some way with the performance of magic. However, the only incontrovertible evidence for the use of ritual masks by the living are found from Egypt's Late Period. From that time, for example, we have a unique, ceramic mask of the head of the jackal god, Anubis (now in the collection of the Roemer Pelizaeus- Museum, Hildesheim), dating to sometime after 600 BC, which was apparently manufactured specifically as a head covering. This mask has indentations on both sides which would have allowed it to be supported atop the shoulders. The snout and upraised ears of the jackal head would have surmounted the wearers actual head. Two holes in the neck of the object would have allowed the wearer to view straight ahead. However, lateral vision would have been limited, thus necessitating the wearer's need for assistance, as explicitly depicted in a temple relief at Dendera. In this depiction, the priest wears just such a mask, and is assisted by a companion priest. A description of a festival procession of Isis, which was led by the god Anubis, who was presumably a similarly masked priest, took place not in Egypt but rather in Kenchreai.

Funerary masks had more than one purpose. They were a part of the elaborate precautions taken by the ancient Egyptians to preserve the body after death. The protection of the head was of primary concern during this process. Thus, a face covering helped preserve the head, as well as providing a permanent substitute, in an idealized form which presented the deceased in the likeness of an immortal being, in case of physical damage. Those of means were provided with both a mask with gilt flesh tones and blue wigs, both associated with the glittering flesh and the lapis lazuli hair of the sun god. Specific features of a mask, including the eyes, eyebrows, forehead and other features, were directly identified with individual divinities, as explained in the Book of the Dead, Spell 151b. This allowed the deceased to arrive safely in the hereafter, and gain acceptance among the other divine immortals in the council of the great god of the dead, Osiris. Though such masks were initially made for only the royalty, later such masks were manufactured for the elite class for both males and females.

Beginning in the 4th Dynasty, attempts were made to stiffen and mold the outer layer of linen bandages used in mummification to cover the faces of the deceased and to emphasize prominent facial features in paint. The forerunners of mummy masks date to this period through the 6th Dynasty, taking the form of thin coatings of plaster molded either directly over the face or on top of the linen wrappings, perhaps fulfilling a similar purpose to the 4th Dynasty reserve heads.A plaster mold, apparently taken directly from the face of a corpse, was excavated from the 6th Dynasty mortuary temple of Teti, though unfortunately, this is thought to date to the Greco-Roman period.

The very earliest masks were experimentally crafted as independent sculptural work, and have been dated to the Herakleopolitan period (late First Intermediate Period). These early masks were made of wood, fashioned in two pieces and held together with pegs, or cartonnage (layers of linen or papyrus stiffened with plaster. They were molded over a wooden model or core. The masks of both men and women had over-exaggerated eyes and often enigmatic half smiles. These objects were then framed by long, narrow, tripartite wigs held securely by a decorated headband. The "bib" of the mask extended to cover the chest, and were painted for both males and females with elaborate beading and floral motif necklaces or broad collars that served not only an aesthetic function but also an apotropaic requirement as set out in the funerary spells. Hollow and solid masks (sometimes of diminutive size) were also built by pouring clay or plaster into generic, often unisex molds. To this, ears and gender specific details were than added. These elongated masks eventually evolved into anthropoid inner coffins, first appearing in the 12th Dynasty.

Masks became increasingly more sophisticated during the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period. These later masks made for royalty were beaten from precious metals. Of course, an obvious example of such is the solid gold mask of Tutankhamun, though we also have fine gold and silver specimens from Tanis.

However, masks of all types were embellished with paint, using red for the flesh tones of males and yellow, pale tones for females. Added to this were composite, inlaid eyes or eyebrows, as well as other details that could elevate the cost of the finished product considerably. Hence, indications of social status, including hairstyles, jewelry and costumes (depicted on body-length head covers) are often helpful in dating masks. However, the idealized image of transfigured divinity, which was the objective of the funerary masks, precluded the individualization of masks to the point of portraiture. The results are that we have a relative sameness in these objects with anonymous facial features from all periods of Egyptian history.

The use of face coverings for the dead continued in Egypt for as long as mummification was practiced in Egypt. Regional preferences included cartonnage and plaster masks, both of equal popularity during the Ptolemaic (Greek) period. The cartonnage masks became actually only one part of a complete set of separate cartonnage pieces that covered the wrapped body. This set included a separate cartonnage breastplate and foot case. During the Roman period, plaster masks exhibit Greco-Roman influence only in their coiffures, which were patterned from styles current at the imperial court. This included both beards and mustaches for males, and elaborate coiffures on women, all highly molded in relief.

However, during the Roman period there were alternatives to the cartonnage or plaster mask. Introduced during this period were the so-called Fayoum portraits, which were initially unearthed from cemeteries in the Fayoum and first archaeologically excavated in 1888 and between 1910 and 1911 by Flinders Petrie at Hawara. Since then, they have been discovered at sites throughout Egypt from the northern coast to Aswan in the south. These were paintings made with encaustic (colored beeswax) or tempera (watercolor) on wooden panels or linen shrouds and were rendered in a Hellenistic style not unlike contemporary frescoes discovered at Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy. Nevertheless, it is believed that such two-dimensional paintings held the same ideological function as traditional three-dimensional masks. However, these portraits were popular among nineteenth and early twentieth century collectors and this had a tendency to at first isolate them from their funerary contexts. They were studied by classicists and art historians who, basing their conclusions on details in the paintings along, such as hairstyles, jewelry and costume, identified the portraits as being those of Greek or Roman settlers who had adopted Egyptian burial customs. In fact, successful attempts have been made, based on the analysis of brush strokes and tool marks and the distinctive rendering of anatomical features, to group these portraits according to schools and to identify some individual artistic hands.

However, though the portraits do appear at first to capture the unique features of specific individuals, it appears likely that only the earliest examples were painted from live models. Studies have indicated that the same generic quality that permeates the visages of the cartonnage and plaster masks persists within the group of Fayoum portraits that have been preserved and therefore we believe that they served in a similar fashion as the earlier masks.

There may also be evidence for a cultic use of these paintings while their owners still lived. The fact that the upper corners of some of these panels were cut at an angle to secure a better fit before being positioned over the mummy, that there are signs of wear on paintings in places that would have been covered by the mummy wrappings, and that at least one portrait (now in the British Museum was discovered at Hawara still within a wooden frame indicates that the paintings had a domestic use prior to inclusion within the funerary equipment. They may have been hung in the owners home prior to such use.

Yet the iconographic elements, including gilded lips in accordance with the funerary spells 21 through 23 of the Book of the Dead to insure the power of speech during the afterlife, as well as the allusions to traditional deities, such as the sidelock of Horus worn by adolescents, the pointed star diadem of Serapis worn by men, and the horned solar crown of Isis worn by adult females, together with other evidence, emphasize a continuity of native Egyptian traditions. Though the product of the Hellenistic age of Roman Egypt, they date from the end of a continuum of a desire to permanently preserve the faces of the dead in an idealized and transfigured form that began in the Old Kingdom and lasted to the end of pagan Egypt.

The last examples we have of funerary masks are actually painted linen shrouds of which the upper part was pressed into a mold to produce the effect of a three dimensional plaster mask. Some examples of this type of object may date as late as the third of fourth century AD. First unearthed by Edouard Naville within the sacred precinct of the mortuary chapel of Queen Hatshepsut, they were initially and incorrectly identified by him as the mummies of early Christians. However, later analysis by H. E. Winlock, particularly noting the ubiquitous representation of the bark of the Egyptian funerary god Sokar, correctly identified these as further examples of masks consistent with pagan Egyptian funerary traditions, even though certain motifs, such as the cup held in one hand, seem to present the final transition from pagan mask to Coptic icon painting and the portraits of Byzantine saints.

reign of Amenemope rendered in gold leaf on bronze

References:

|

Title |

Author |

Date |

Publisher |

Reference Number |

|

Ancient Gods Speak, The: A Guide to Egyptian Religion |

Redford, Donald B. |

2002 |

Oxford University Press |

ISBN 0-19-515401-0 |

|

Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, The |

Wilkinson, Richard H. |

2003 |

Thames & Hudson, LTD |

ISBN 0-500-05120-8 |

|

Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, The |

Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul |

1995 |

Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers |

ISBN 0-8109-3225-3 |

|

Egyptian Book of the Dead, The (The Book of Going Forth by Day) |

Goblet, Dr. Ogden |

1994 |

Chronicle Books |

ISBN 0-8118-0767-3 |

|

Mummies Myth and Magic |

El Mahdy, Christine |

1989 |

Thames and Hudson Ltd |

ISBN 0-500-27579-3 |

|

Tutankhamun (His Tomb and Its Treasures) |

Edwards, I. E. S. |

1977 |

Metropolitan Museum of Art; Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. |

ISBN 0-394-41170-6 |