Two Men Named Nakht

By Marie Parsons

Hetep di Nisut-An offering which the king gives to Osiris, lord of the West and to Anubis, guardian of the necropolis. A thousand of beer, a thousand of bread, a thousand of fowl, a thousand of cattle, a thousand of cool water, a thousand of alabaster, a thousand of every good and pure thing be to the ka of the Observer of the Hours, the Scribe Nakht, justified, and to the ka of the little weaver, Nakht.

-a derivation of the offering formula made to respect the dead named herein.

The name Nakht means "the strong one." Several men named Nakht are known, one in the Middle Kingdom and others in the New Kingdom. Most held positions of some note within the Egyptian bureaucracy.

So much of the time, attention is given to the treasures and actions of the kings, their armies, and their diplomatic lives. The focus is usually on the burial process and ceremony undergone by the kings. After all, so much of the mystery and exotic ambience of Egypt that we feel today comes from the rich gold, jewelry, great monuments, and "legendary curses" that fuel movies and the modern western mind.

If we take notice of "lesser beings" such as viziers, governors, and other nobles, we want to know of their treasures, and their activities as far as where they fit in with the King of the time.

But sometimes even what we "know" of the upper classes is truly nothing at all. All we have is quantity, not quality. Sometimes, what we know of the common people, the workers, bakers, weavers, stonemasons, gives us a richer picture of ancient Egyptian life, and make us feel more akin to these people from five millennia ago.

Two particular men, both named Nakht, illustrate this point. One was a humble weaver, who told us much of his life even after the passage of millennia. The other Nakht was a temple Scribe, with an honored position. Let us look first at Scribe Nakht.

Our first Nakht was a scribe and "Observer of the Hours of the night" at the Temple of Amun, which meant he was either an actual astronomer, or at least he was responsible for assuring that rituals were carried out at the correct times. He was married to a woman named Tawy, who herself held the position of "Chantress of Amun," meaning she was a temple musician, an honored position in itself.

Nakhts tomb has been found in Thebes, along with many others, and studied. It contains a number of now fairly familiar scenes of daily life. When the tomb was originally discovered, a number of objects were noted in the burial chamber, and removed for transportation. One object was a kneeling statuette, depicting Nakht holding a stela with a hymn to the sun god Re. Unfortunately, the ship carrying the funerary equipment was torpedoed and sunk during WW I, so nothing is left of the originals.

The tomb has been dated to the end of the reign of Tuthmosis IV or even into the early years of Amenhotep III, based upon artistic conventions such as large almond-shaped eyes, tip-tilted noses, and sinuous bodies of the women painted on some walls.

The tomb itself was never finished. The passage was only plastered, not painted, so it contains no funerary scenes, as would be seen in other tombs nearby. There may never have been a statue made for the statue niche.

The only part of the tomb painted is the reception hall (vestibule). Its ceiling has a carpet-pattern and just below, at the top of the wall, is a kheker-frieze, a decorative border. The paintings in this hall, which will be described and shown below, are idealized visions of not just the life of Nakht and his wife and family, but they were traditional motifs in other tombs as well. For example, the deceased and his spouse and family is always shown dressed for a festival, white kilts or dresses and jewelry, hair elegantly dressed, bodily postures tall and straight.

So, as true windows into his actual life, the paintings fall short. But they are lovely nonetheless. And they contribute to the image of peaceful, tranquil, almost "magical" lives so often attributed to these exotic Egyptians.

Just to the left of the entrance to the hall heaps of offerings are depicted on two mats. The lower mat is covered with grapes, fowl, vegetables such as lettuce and cucumbers, loaves and choice bits of beef, such as haunches and ribs. The dietary choices in Egypt were certainly plentiful. Four tall vessels, decorated with lotus blossoms, stand on the upper mat and held oils and ointments. Nakht is shown pouring a brown mass of myrrh over the offerings. Behind Nakht is his wife holding a sistrum and menit, traditional instruments for temple musicians. Among the offerings, the front leg of a black-checked cow is being cut off. A man is turning to Nakht in the painting, passing him incense.

Accompanying this scene is an inscription: "Offerings of every good, pure thing, bread, beer, cattle, fowl, long-horned and short-horned cattle, thrown upon the brazier for Amun, for Ra-Harakhte, for Osiris, the great god, for Hathor above the desert, for Anubis on top of his mountain, by the Observer of the Hours of Amun, scribe justified and his wife, beloved of the seat of his heart, the Chantress of Amun, the Mistress of the House, justified." This caption is reminiscent of the Offering Formula. These scenes are always found in the front room of the tomb, linking the deceased to the world of the living.

Ordinary workers and life in the countryside are shown in another scene, entitled "Sitting in a booth, viewing his fields by the Observer of Hours, justified before the great god." Nakht is depicted here, sitting under a canopy. Unkempt workers, distinguished by unkempt hair and plain kilts, are hoeing the earth and sowing grain. A tree is being cut down, though the woodcutter is taking a break for a drink.

When the grain is ripe, it is cut with sickles just below the ears, and the ears are then placed in baskets to be measured. A worker is seen trying to lift the basket. To the left, two girls, wearing the standard clean white linen, are plucking flax. Two other workers are measuring grain under the watchful eye of a supervisor.

When the harvest was finally delivered and registered, the chaff is separated from the wheat. The winnowing is done by rows of men lined up as they toss the grain in the air. White cloths protect their heads from the dust that accompanies the process.

The measuring and winnowing are being done with Nakht again in witness, sitting under a canopy. This scene is perhaps a symbolic guarantee that sufficient fresh bread and food will be available in the Beyond. And cultivating the "fields of the blessed" is an important part of Spell 110 in the Book of the Dead.

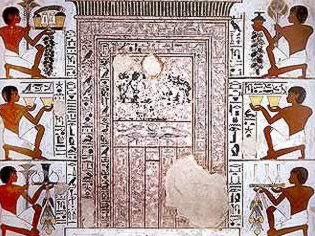

At the left end of the hall is a false door. Here the tomb-owners descendants responsible for his mortuary cult would deposit their offerings. But Nakht and his wife apparently had no surviving children, at least, none depicted in this scene. Instead, the servants are making the offerings. One brings lotus blossoms, bread, vegetables, grapes and water; another brings ointments, incense and flowers. To the right, papyrus, beer, wine and clothes are being offered.

Below the false door is a heap of offerings, fruit loaves, meat, fowl, papyrus, and lotus. On either side of the offering pile stands a man and a woman. The womans head is symbolically topped with a fruit-bearing tree, perhaps connected to Spell 59 of the Book of the Dead, where the deceased hopes to breathe air and control water through the sycamore goddess, Nut.

There are also the banquet scenes. A blind harpist with crossed legs is depicted to the right of a group of three elegantly dressed ladies, seated on mats. There are also three female musicians, one playing a double oboe, one playing harp, and one playing a lute. Each woman wears rich jewelry and wigs.

To the right, beside the passage, Nakht and Tawy are seated before generously laid tables. Tawy has placed one hand on his shoulder and grasps his arms with the other, in a sign of universally understood intimacy and loyalty. Nakht himself sniffs a lotus blossom.

There is another scene of hunting in the papyrus thickets. The hunt has been a common part of tomb decoration since the Old Kingdom, a thousand years earlier. Nakht is shown launching his throw stick at birds while his wife and two children look on. The caption reads: "Enjoying and beholding beauty, spending leisure with the work of the marsh goddess by the confederate of the Mistress of the Catch, the Observer of Hours of Amun, the Scribe Nakht, justified. His wife, the Chantress of Amun, the Mistress of the House, Tawy, says, "Enjoy the work of the goddess of the marsh. Waterfowl were assigned to him for his time.""

To the right of that scene, Nakht is spearing fish. The caption reads, "Crossing the marshes and wandering through the swamps, amusing himself with spearing fish, the Observer of Hours, Amun, justified."

In another scene, Nakht stands in a boat, watched by his wife and three children. It is not clear if these were representations of real children, who may have died after the paintings were complete and thus could not sustain the funerary cult for Nakht, or if these were a fiction for the afterlife.

Nothing is known of Nakhts work, how he served his office in the temple, what prayers he may have offered, when he died, if he had illnesses or misfortunes. His name appeared to be effaced in places within the chamber, so possibly he fell out of favor at some time.

More is known of another named Nakht, this one a young boy of the peasant class. What is known of him is possible only because his corpse, unembalmed, was donated as part of a study of ancient bodies to learn more about the physiological conditions known to the ancient Egyptians.

Nakht the weaver had been laying in his humble wooden coffin, stashed in the Royal Ontario Museum museums basement storeroom. When studies demanded a body about which at least the provenance was known, and the location where it had been found, the curator of Egyptology offered Nakht for examination.

Nakhts coffin had been brought back from Egypt at the beginning of the 20th Century, by the first director of the museum. Hieroglyphic inscription on the coffin date it to the 20th Dynasty in the New Kingdom. Nakht was a Theban weaver, who had worked at the temple of King Setnakhte, the dynastys founder.

Nakht was not an actual mummy. All his internal organs were in place, so he had not been embalmed, but had merely been simply wrapped and placed in his coffin and left to the dry Egyptian climate. Since mummification was an expensive enterprise, this was not surprising for a poor weaver.

Nakhts bone development showed that he was probably a young teenager, about 15 years old. He weighed in at 11.3 pounds. His body was still growing, and he stood at 4 feet 8 inches tall. However, tell-tale lines of arrested growth on his shin bones hinted at malnutrition or possibly a prolonged illness with high fever. Every person acquires such stress lines when we become ill, as our growth temporarily slows. But Nakhts stress lines were more frequent and more visible than normal.

After his linen bandages, which had not been soaked in resin, came away easily, each long strip was rolled up and saved for later analysis.

The concave depression in Nakhts shrunken abdomen had been filled out with two shirts, sleeveless tunics of the sort the weaver had probably worn, and that were part of his personal wardrobe. These garments were also laid aside for textile analysis.

Nakhts body was in reasonably good condition. Its skin was intact and possessed a tough, leathery consistency. He was probably lovingly prepared for his humble burial, as his face had been shaved before burial and his nails had been trimmed. His toenails in fact were in excellent condition, even though one foot bore a well-developed plantar wart. His skull was also badly damaged, the facial bones having collapsed into the cranial cavity after burial.

Nakhts internal organs proved to be in place and mostly intact. His heart was still attached to the sternum and liver was easily identifiable, though shrunken. His kidneys, bladder and prostate were all in one piece. His bowel had survived but was as flimsy as tissue paper. In the worst shape were the collapsed lungs and the enlarged spleen, surrounded by a dark mass, suggesting malaria.

Brains were generally never found in mummies because the tradition was to remove the brains from the Middle Kingdom onward. But as it turned out, since Nakht had not been embalmed, his brain was also discovered within the cranial cavity. It had been preserved by a naturally occurring chemical process called hydrolysis, which converts the fat in human tissue into a waxy substance. Nakhts brain, with each of the two hemispheres separated but intact, is now the oldest intact human brain ever found.

The young boy had suffered from black lung disease and desert lung disease. The sand particles in his lungs were red granite, occurring only at Aswan, many miles upriver from the town of Thebes. A tapeworm and its many eggs were found in his intestines, indicating that he had been a meat eater. He also had trichinosis, proof that he ate pork. He was also infected with schistosomiasis, the parasite laying eggs in the bladder and the liver, giving him cirrhosis. And pneumonia was what probably killed him, starving his already damaged lungs.

In the Satire of the Trades, also known as the Instruction of Khety, the writer describes the life of a weaver: "His knees are drawn up against his belly. He cannot breathe the air." In Nakhts case, his life was indeed humble and careworn. Was he less better off than the astronomer-scribe Nakht? Who can say.

Sources:

- Life and Death in Ancient Egypt by Sigrid Hodel-Hoenes

- Conversations with Mummies by Rosalie David and Rick Archbold

- Literature of Ancient Egypt ed. By William Kelly Simpson

Marie Parsons is an ardent student of Egyptian archaeology, ancient history and its religion. To learn about the earliest civilization is to learn about ourselves. Marie welcomes comments to marieparsons@prodigy.net.

last updated: June 8th, 2011