by Jimmy Dunn writing as Alan Winston

They had been cooling their heals on the terraces of the Longchamps Hotel for just about a month. Stephen Harvey and his gang from the University of Memphis had their permissions to excavate, but lacked the security clearances needed to move the group to Abydos where they would continue the excavation of Ahmose I's pyramid and mortuary temple. They all seemed to be enjoying their stay in Egypt, but there was clearly a mounting anxiety that the digging season, as well as their funding would run out before they ever began.

This group, actually operating under the aegis of the University of Pennsylvania-Yale Institute of Fine Arts and the New York University Expedition to Abydos, hasn't the big profile of groups such as Kent Weeks, but rather represents the more typical, often under funded archaeological expeditions one sees doing important, but sometimes neglected work throughout Egypt.As Stephen Harvey explains, state of the art technology generally becomes available to them when it hits the local Radio Shack, and their digging season begins when the high profile groups take off during the heat of the summer. Yet they have an important project that has already yielded considerable and valuable contributions to our understanding of Egyptian history around the end of the Hyksos occupation of Egypt.

We had big plans for interviewing various members of the group, but then suddenly the security clearances were provided, and seemingly in the blink of an eye, they were off to the dig. Well never fear. We made arrangements to follow this dig and the group's work, so we will be revisiting their efforts as their excavations continue.

Almost all of Egypt's pyramids are located within a short day trip from Cairo in Lower Egypt. Indeed, most of Egypt's pyramids can be found within the confines of four or five sites, including Giza, Saqqara, Dahshur, Abusir and Abu Rawash. If we include the pyramids just east of the Fayoum region, we account for all of Egypt's pyramids with the exception of only a few scattered about in other locations, of which only a meager few are to be found in southern Egypt. Hence, even though mostly small, these southern pyramids hold a certain interest and intrigue. Most of them are thought to have not functioned in the same manner as their larger northern cousins. Seemingly, they usually do not have mortuary complexes attached, and some seem to lack any substructure. Many Egyptologists believe that they functioned as regional monuments to the king, perhaps built in the region of their rural palaces. However, the pyramid that Stephen Harvey and his group are excavating seems to be one of the exception.

Ahmose I's pyramid at Abydos is generally considered to be the last such royal complex built in Egypt. However, it has a number of other distinguishing attributes, including the first known representations of horses and complex chariot warfare.

A depiction of Egypt's first horses

Three archers in the army of King Ahmose

This complex was originally investigated by Arthur Mace and Charles T. Currelly for the Egypt Exploration Fund between 1899 and 1902, but their work was very partial and all that they left us was a sketch map of the general location without identifying the location, size or extent of Ahmose's pyramid and related structures. While this early team did excavate a large part of the mortuary temple's interior, they only published two stone architectural fragments.

Therefore, Stephen Harvey's team was surprised to find thousands of inscribed fragments when they began work in 1993 on the site. Most of the fragments were corners and edges of blocks. One set of relief fragments on the eastern side of the inner court included a representation of a group of three tightly massed archers firing arrows, with teams of bridled chariot horses, ships with oar descending into water, and fallen men recognizable by their characteristic fringed garments and long swords as Asiatic soldiers (probably Hyksos). Some small fragments bore the names of Apophis, who was Ahmose's principal Hyksos opponent, and Avaris, the Hyksos capital. The excavators believe that these scenes represent the only known contemporary visual record of Ahmose's struggles against the Hyksos.

Actually, Stephen discovered two principle types of reliefs at the site. One style characterized by high raised reliefs carved in chalky white limestone and painted in bright pastel colors, can be ascribed to the actual reign of Ahmose, while a second style, more classic in nature with unpainted low raised reliefs, is probably from the reign of Amenhotep I, the son of Ahmose.

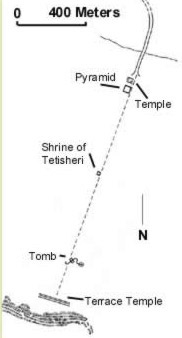

The Complex

The ruins of Ahmose at Abydos are extensive, not only consisting of a pyramid and mortuary complex, but also the town of the workers who built and later managed the facilities. The mortuary temple that is recognizable as such lies somewhat north of the pyramid. This structure appears for the most part to be the outer section of the temple, with a plan consisting of a massive wall on the east and a central doorway that lead to a forecourt. From the forecourt, a doorway leads to a square court. Foundation blocks at the back might have supported the pillars of a colonade. However, between this section of the temple and the pyramid itself are what probably remains of an inner court where little was found except patches of pavement and four circular granaries along the back wall. Mace also discovered a semi-circular mudbrick deposit that may have either been the remains of a ramp, or the inner sanctuary of the temple.

At the southeast corner of the pyramid, a second smaller temple was also discovered that was probably dedicated to Ahmose's sister-wife, Ahmose-Nefertari.

The pyramid had a core built of sand and loose stone rubble, which, after having lost most of its outer casing, fell into ruin. Originally, it was probably some 52.5 meters (172 ft) square with a similar or slightly smaller height. Mace estimated, from the remains of two intact courses of casing stones that survived at the eastern base of the pyramid, that its slope measured about 60 degrees. Neither Mace, nor the later excavations by C. T. Currelly, revealed any internal (or apparently actual substructure) chambers.

On a line back nearly south of the pyramid and mortuary complex also lies a shrine that was dedicated to Tetisheri, who was Ahmose I's grandmother. This structure is a massive budbrick building with a shape not unlike that of a mastaba. A corridor lead through the center of the building to a remarkable stela inscribed by Ahmose at the rear. It includes two depictions of Tetisheri, and hieroglyphic text of the kings intentions to build a pyramid in memory of his grandmother.

Further southward, and on a line with the shrine to Tetisheri, and Ahmose's pyramid complex is a tomb, perhaps a cenotaph, or false tomb, built by Ahmose. This structure carved into the bedrock was rather quickly and poorly done, perhaps being only a token Osirian underworld. The entrance is a pit relatively small in size, that leads to a low, initial horizontal passage. Rooms on both sides of the corridor are crudely shaped and left unfinished. The corridor eventually leads to a hall with a total of 18 pillars.

Finally, southward from this tomb on the same line as the pyramid and the Tetisheri shrine is a set of terraces built against the high cliffs. The bottom terrace is made of bricks and measured 300 feet in length, with a second terrace of rough field stone on a second level. It is likely that these terraces were meant to support a temple, perhaps reminiscent of that built by Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. A cache of votive ceramic vessels, model stone vases and boats with oars were buried near the south end.

a fragment bearing the name of the Kyksos king, Apophis (Ipep)

Even though Ahmose I's mummy was probably found at Thebes, Stephen Harvey seems to believe, because of the extensive ruins of Amhose at Abydos, that it is possible the king was originally buried in that holy place. No tomb of his has been discovered in the Valley of the Kings at Thebes (modern Luxor).

What is more certain then the burial place of King Ahmose is that we will be continuing to update you on this dig, as well as some of the archaeological processes, so look for more information soon.

See also:

References:

|

Title |

Author |

Date |

Publisher |

Reference Number |

|

Lehner, Mark |

1997 |

Thames and Hudson, Ltd |

ISBN 0-500-05084-8 |

|

|

History of Ancient Egypt, A |

Grimal, Nicolas |

1988 |

Blackwell |

None Stated |

|

Shaw, Ian |

2000 |

Oxford University Press |

ISBN 0-19-815034-2 |