Known as the Mosque of al-Guyushi

by Jimmy Dunn writing as Ismail Abaza

One of the oldest Muslim monuments in Egypt sits high up on the plateau of the Muqattam hills overlooking the cemetery of Cairo, as well as Cairo itself. This is the sanctuary of Badr al-Jamali (Badr al-Gamali, al-Jammali), an Armenian who was prior to his time in Egypt, the governor of Acre. Al-Jamali became not only vizier to the Fatimid Caliph al-Mustansir (1036-1094), who had requested his help in restoring order to Egypt, but also held the honored title, "The Great Master, Prince of Armies". He is notable for having rebuilt al-Qahira's (Cairo) defenses. In order to reach this mosque, one must take the road which turns right off Salah Salim to Muqattam City, opposite the eastern entrance to the Citadel fortress.

This monument is somewhat of a mystery to us. We refer to it as a mosque, but an inscription on its foundation above the entrance describes it as a mashhad, or shrine, though no one is known to be buried here, and there is no indication in who's memory it was built. Yet, there is a small domed chamber projecting from the northern side of the sanctuary that could have at least been intended as a mausoleum. Creswell thought this was a later addition, but Farid Shafi'i proved that it was part of the original construction. The Description de l'Egypt defined the monument as the "chapel of Shaykh Badr" on a map, which could have been a popular version of al-Jamali's name. A street in the same area is called Shaykh Najm, and Abu 'l-Najm was one of the honorific titles of Badr al-Jamali. However, Maqrizi tells us that Badr al-Jamali was buried outside Bab al-Nasr (Gate of Victory).

Its setting is isolated from the main pilgrimage centers of the Southern Qarafa, and so its purpose remains obscure. It has been suggested that it acts as a watchtower disguised as a mosque, because of the exaggerated size of the minaret and the appearance on the roof of domed edicules too small for any religious function. The two small domed structures, almost like kioks less than one meter in width, with prayer niches carved on their southeastern sides, could have been for guards. One must remember that al-Jamali was the commander of Egypt's armies.

However, others see it as a memorial to the victories of Badr al-Jamali over the chaos that had long troubled the Fatimid Empire. They see the small domes atop the structure as simply small rooms for meditation and seclusion as the location of the mosque obviously provided. Regardless of these theories, the novel composition of its forms, along with their miniature size, especially when perceived in its particular setting, lead us to few firm answers.

Perhaps because its builder was not particularly important religiously, the building was never used as an important cult center, and has therefore aged well. Usually, such buildings would have been subjected to a number of restorations and embellishments. However, during the Ottoman period, the mosque was used by dervishes as a monastery. Nevertheless, it is the most complete mashhad that has survived from the Fatimid period.

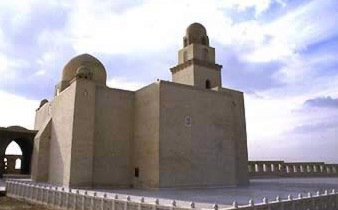

This is a symmetrical rectangular structure measuring 22.5 by 17 meters, built of rubble masonry and brick. It is built around a very small courtyard. One enters it through a plain door, significantly lacking a portal, underneath the minaret situated on the axis of the prayer hall.

This Syrian inspired minaret some 20 meters high, which is the oldest surviving minaret of its kind in Cairo, has a tall base, a square second story, an octagonal third story that is then surmounted by a dome. On both sides of the minaret are rooms. The minaret's shape is reminiscent of the minaret at the great mosque of Qayrawan in Tunisia, which was erected in the ninth century. The cornice of niches in a double row around the first story (muqarnas cornice) marks the first appearance of stalactite decorations, an adornment that would appear frequently in later buildings. It is employed here to emphasize the visual separation of the various parts of the minaret. Since the second occurrence in Egypt of this muqarnas feature, which is in the wall of Cairo next to Bab al-Futuh (Gate of Conquest), is also attributed to the Armenian vizier and former governor of Syria, Badr al-Jamali, it has been suggested that this Persian motif was introduced into Egypt through Armenian and Syrian mediation.

Within, the facade of the courtyard is composed of a large keel arch supported by two pairs of columns and flanked by two smaller arches, giving the facade the tripartite composition often found in Fatimid structures. A transitional, cross-vaulted vestibule, defined by a triple-arched portico on its courtyard side, leads to the square dome chamber as well as to two cross-vaulted extensions flanking the courtyard. It has been suggested that these rooms to either side of the courtyard were for residential purposes, since they do not provide access to the prayer hall.

The Prayer hall itself is roofed over with cross vaults though the bay above the prayer niche is crowned by a dome on plain squinches. The real beauty of this building is the mihrab of carved stucco. The niche is lavishly decorated with stucco carving in the spandrels of its arch. The conch itself has eighteenth century Ottoman paintings of lowers, framed by a rectangular panel in which bands of Quaranic inscriptions alternate with arabesque leaf patterns. Creswell believed that this decoration is comparable to Persian designs. The interior of the dome here is also decorated with stucco carving and at the summit is a medallion with the names of Muhammad and 'Ali. On the square part of the dome, an inscription band carries a Quaranic text.

Not long ago, this monument was restored by Dawoodi Bohras.

A more recent photo of the structure prior to its restoration

References:

|

Title |

Author |

Date |

Publisher |

Reference Number |

|

Cambridge Illustrated History Islamic World |

Robinson, Francis |

1996 |

Cambridge University Press |

ISBN 0-521-43510-2 |

|

Historical Cairo (A Walk Through the Islamic City) |

Antonious, Jim |

1988 |

American University in Cairo Press, The |

ISBN 977-424-497-4 |

|

Islamic Monuments in Cairo, A Practical Guide |

Paker, Richard B.; Sabin, Robin; Williams, Caroline |

1985 |

American University in Cairo Press, The |

ISBN 977 424 036 7 |

|

Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction |

Behrens-Abouseif, Doris |

1992 |

E. J. Brill |

ISBN 90-04-08677-3 |

|

Mosque, The: History, Architectural Development & Regional Diversity |

Frishman, Martin and Khan, Hasan-Uddin |

1994 |

Thames and Hudson LTD |

ISBN 0-500-34133-8 |