The Mosque of Sulayman Pasha al-Khadim at the Citadel in Egypt

by Jimmy Dunn writing as Ismail Abaza

Though not the first religious foundation founded in Cairo after the Ottoman conquest, the Mosque of Sulayman (Suleyman) Pasha al-Khadim was, in 1528, the first mosque built by the new rulers. The mosque is located in the northern enclosure of the Citadel, near the far (eastern) end, which was at the time occupied by the Janisssary corps of the Ottoman army. A provision that the Sheikh of the mosque had to be Turkish indicates its dedication to this corps. Sulayman Pasha was a court eunuch who eventually became wali (governor) for the corps of Janissaries.

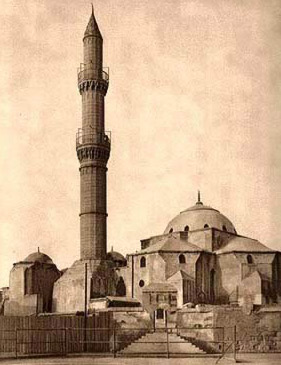

Though small, the mosque is a fine example of early sixteenth century Ottoman architecture. It is a center0dome, free standing structure located in a garden enclosure.

The mosque's architecture owes very little to Cairene traditions and its plan, in the form of an inverse-T, is entirely early Ottoman with the mihrab located in the stem of the T. It is a rectangular building, about half of which is taken up by the prayer hall, while the other half consists of the courtyard.

The building has no facade in the Cairene architectural sense of paneling and decorative fenestrations. Perhaps because of its military heritage, the mosque's appearance is rather introverted. Its small, unimpressive portal appears to be an imitation of the nearby al-Nasir Muhammad's mosque, also in the Citadel, with a half dome on stalactites. The minaret, which includes a high cylindrical faceted shaft which was new to Cairo, stands to the left of the entrance on the south wall of the sanctuary. It uses a Mamluk device in the different styles of stalactite carving on the balconies, an exception among Cairo's Ottoman minarets. The profile of the dome is rounded and squat.

Within, there is no vestibule. The entrance which is used today, which is not the main entrance, leads directly into the prayer hall. The prayer hall is a rectangular space covered by a central dome, flanked by three half-domes, much like that of the Muhammad 'Ali Mosque. The dome in Ottoman mosques was used to cover the whole sanctuary of the mosque instead of just the mausoleum annexed to it or only the part in front of the mihrab. The central dome rests on spherical pendentives. Its painting and that of the transitional zone have been restored. A handsome inscription encircles the dome, a prominent and elevated place for the written word, the basis of the Universal Law of Islam, (Quran 3:189-194):

"To God belongs the Kingdom of the heavens and of the earth; and God is powerful over everything.

Surely in the creation of the heavens and earth and in the alternation of night and day there are signs for men possessed of minds who remember God;

Standing and sitting on their sides, And reflect upon the creation of the heavens and the earth:

'Our Lord, Thou has not created this for vanity, Glory be to Thee!

Guard us against the chastisement of the Fire.

Our Lord, whomsoever Thou admittest into the Fire, Thou wilt have abased; and the evildoers shall have no helpers.

Our Lord, we have heard a caller calling us to belief, saying, "Believe you in your Lord!" And we believe.

Our Lord, forgive Thou us our sins and acquit us of our evil deeds, and take us to Thee with the pious.

Our Lord, give us what Thou has promised us by Thy Messengers, and abase us not on the Day of Resurrection:

Thou wilt not fail the tryst."

Like in the nearby Muhammad 'Ali Mosque (also Ottoman), the large medallions which interrupt the inscription contain the names of God (Allah), Muhammad, Abu Bakr, 'Umar, 'Uthman and 'Ali. Inscribing these names in dominant medallions, often drawn by famous calligraphers, is a feature of Ottoman mosques begun at a time when the Ottoman empire's chief rival was the Shi'i Persian empire of the Safavids. The purpose is thus hortatory and religious more than decorative. They remind the faithful of Sunni orthodoxy.

The dikka is attached to the upper part of the wall facing the prayer niche and is reached by an inner staircase. It is also painted. A large pulpit (minbar), carved and painted, is surmounted by a conical top like that of the minaret, just as Mamluk pulpits had pavilions similar to those of their minarets. The pulpit is composed of panels of marble held together by iron cleats and is decorated with a geometric pattern based on stars and polygonal forms, both the material and pattern inspired by Mamluk work.

The lower part of the inner walls of the Prayer Hall are covered with marble dadoes in Mamluk style and a frieze of carved marble inlaid with paste runs above the dado. The walls were restored in the nineteenth century. It is not certain how faithful they are to the original Ottoman decorations, but a rich effect is achieved.

Much of the remainder of the decorations hark back to Mamluk precedents, including the projecting loggia upon molded corbels and the simulated marble veneer made of bitumen and red paste in the grooved inscription around the walls.

A door in the western wall leads to a courtyard paved with marble. The vault above the entrance to the courtyard is worth noticing. The stucco arabesques and half-palmettes (a stylized palm leaf used as a decorative element) act as frames for painted floral designs. This emphasis on floral motifs, rather than on geometric or arabesque ornament, was new in Cairo and was brought in by the Ottomans.

The courtyard is surrounded by an arcade covered by shallow domes. The central dome, the shallow domes around the courtyard and the conical top of the minaret are all covered with green tiles. On the west side of the courtyard is a shrine built in the Fatimid period around 1140 by Abu Mansur ibn Qasta to house his tomb. It was dedicated to Sidi Sariya, a companion of the Prophet. The shrine is incorporated into the architecture of the mosque, and covered by a dome larger than those around the courtyard. The shrine includes the tombs of Ottoman officials with cenotaphs topped with various types of turbans in marble. Until recently, there was a wooden boat hanging above the cenotaph of Ibn Qasta. It is a popular tradition in Egypt to place boats in saints' shrines.

On the north side of the courtyard another entrance leads to a second courtyard in front of a vaulted oblong building composed of two halls. The outer hall opens to the courtyard and leads through a door into the inner hall. Both are roofed with two half domes on spherical pendentives, facing each other. According to the foundation deed, this building is a kuttab. Its domes were covered with blue tiles. The kuttab has a prayer niche with stalactites in the conch. At one time, there was apparently also a sabil, though it is no longer extant.

Resources:

|

Title |

Author |

Date |

Publisher |

Reference Number |

|

Al Qahira |

Sassi, Dino |

1992 |

Al Ahram/Elsevier |

None Stated |

|

Cambridge Illustrated History Islamic World |

Robinson, Francis |

1996 |

Cambridge University Press |

ISBN 0-521-43510-2 |

|

Historical Cairo (A Walk Through the Islamic City) |

Antonious, Jim |

1988 |

American University in Cairo Press, The |

ISBN 977-424-497-4 |

|

Islamic Monuments in Cairo, A Practical Guide |

Paker, Richard B.; Sabin, Robin; Williams, Caroline |

1985 |

American University in Cairo Press, The |

ISBN 977 424 036 7 |

|

Mosque, The: History, Architectural Development & Regional Diversity |

Frishman, Martin and Khan, Hasan-Uddin |

1994 |

Thames and Hudson LTD |

ISBN 0-500-34133-8 |